What should police do? Solving crimes, not running community centers, is the direct route to reducing crime and improving trust.

On a cold day in February 2020, the civilian commissioners of a half dozen New York City agencies gathered in the Jack Maple CompStat Center at the New York Police Department headquarters. These were not the usual suspects summoned to this storied room. The CompStat "room," a triple-height hall, with tables set up in a U-formation oriented toward giant TV screens, could swallow up the several hundred people who would fill it.

Since 1994, it has been an arena of both ordeal and triumph: police commanders from across the city gather weekly to go over crime data projected on jumbotrons around the room to figure out whether deployment is working. The room is named after Jack Maple, a deputy commissioner in the Police Department in the 1990s who is credited with being the brains behind the department's wildly successful crime-reduction strategy. He had famously scribbled on a napkin the core elements of the effective policing that CompStat was to ensure. Accurate, timely intelligence. Rapid deployment. Effective tactics. Relentless follow-up.

Over the years, the police have become the first line of response in many areas that seem a step and more away from traditional police services.

But on this day, it was not police commanders being called to account. Instead, the ranks of the invited included the commissioners of the parks department, the youth, social and homeless services agencies and the public housing head. The issue was youth, and, as soon became clear, not just youth crime. Instead, the police commissioner and his deputies laid out an ambitious plan that included the transfer of hundreds of officers and a citywide, multiple-agency focus on youth to "save" them from a life of crime. As the commissioner articulated later, as part of the eventually formalized "Kids First" program, "Part of our calling is to help kids make better choices, expand opportunities and help them reach their fullest potential."

But is it?

Some of the commissioners shifted uneasily in their seats. The presentation revealed the long-standing fault lines between the police and the service agencies. For many, it seemed strange to have the police running this table to help youth, when the tables could turn in an instant for the police to do their "real" job if one of the kids they were saving — or their friends or family — turned out to have committed a serious crime.

Adding to the role confusion, this effort was running alongside previous efforts, including a civilian-run "Children's Cabinet" that counted many of the same commissioners among its members. It raised a fundamental question: why the police?

Over the years, the police have become the first line of response in many areas that seem a step and more away from traditional police services: responding to mental illness crises, clearing homeless encampments and the like. The police are one of the few bodies that operate 24/7/365. When we call for help, the help that arrives is almost always armed.

In New York, the entry of the police into the most intimate sphere of human connection — how children and young people grow up — passed almost without mention.

The past few years have seen a lot of effort devoted to determining how and whether we should wean ourselves from this approach. This has been an area of hot debate in New York City — where both cops and those in crisis have died in the course of these encounters — and across the nation, where different models of response are being deployed.

But in New York, the entry of the police into this most intimate sphere of human connection — how children and young people grow up — has passed almost without mention. It is as if we have accepted the mythical notion of a bygone era of Officer Friendly benevolently overseeing the neighborhood.

We shouldn't.

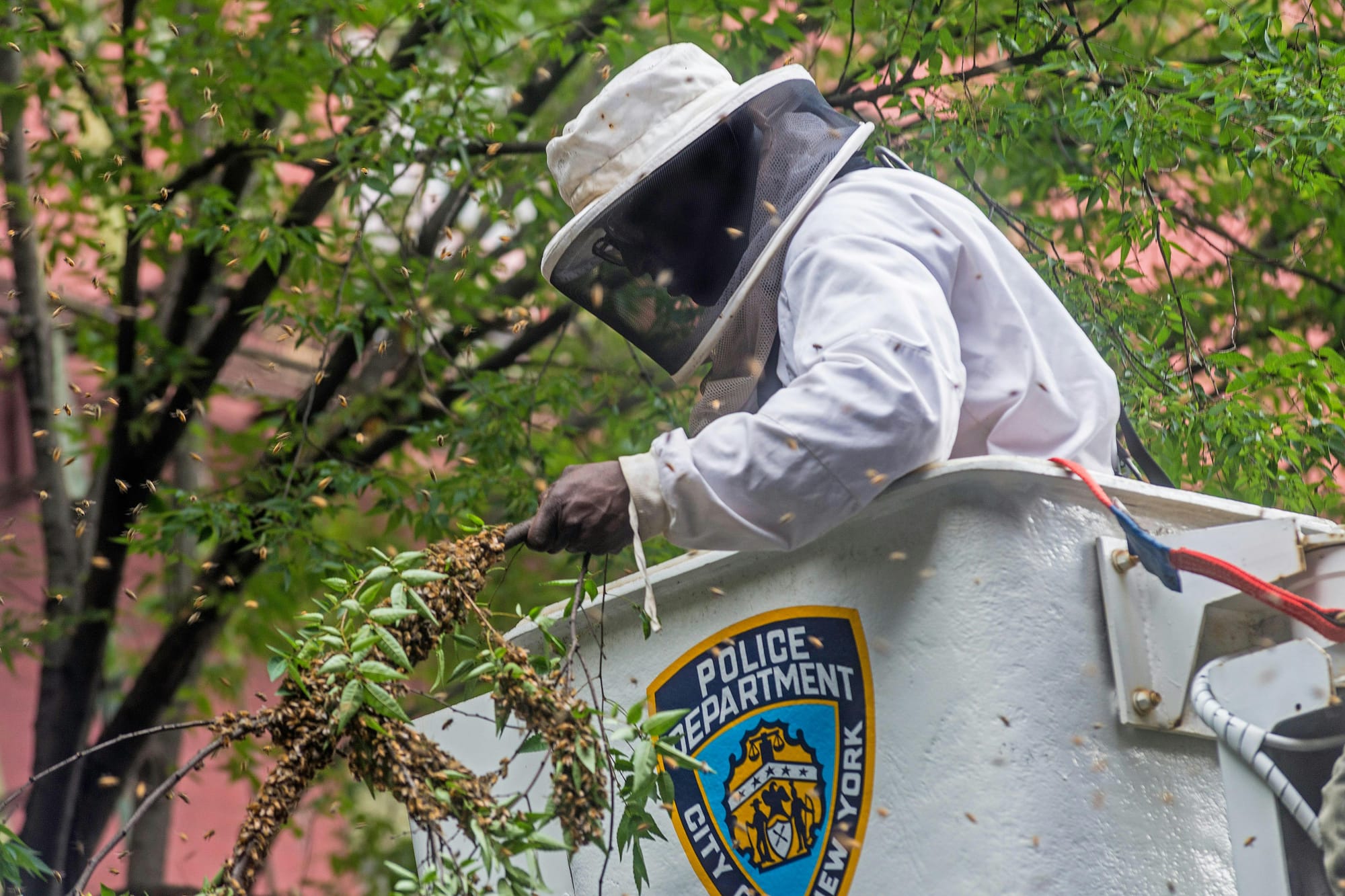

The police have now crept into almost every aspect of civic life. Today, the expansive police program includes the building and staffing of a community center and the creation of basketball courts across the city, the funding of sports, employment and girl-empowerment programs, internships, lessons in everything from dancing to wig-making and coding. The police employ a beekeeper and, as one senior official told me in wonder, a special tree-cutting unit.

Perhaps this accretion of functions has occurred because the police are able to function with a military precision unavailable to civilian agencies? Or because of the extraordinary richness of their budget, which, at almost $11 billion, is the size of the total budget of many states? Or because of their staffing, which, at 36,000 officers and 19,000 civilians, dwarfs some countries' armies?

Whatever the rationale, there are good reasons why the police should stay in their lane instead of taking on an ever-broader swath of civic life. City government exists to provide for its residents' well-being. Our democracy is, and should be, a quintessentially civilian venture. This is why, at the national level, the Joint Chiefs of Staff report to the civilian president. Generals advise but presidents decide. The same goes for cities where the civilian power of the mayor is dominant not just because this is what democracy demands, but also for the simple, practical reason that the civilian head of government has a panoramic view over all city services and thus the unique capacity to weave them together into a single heterogeneous strategy.

The use of force sets cops apart. They are different. They are special. Where one side has the justifiable power to detain or arrest, it creates an inherently unequal relationship. It is this inherent inequality that makes the proposition of neighborhood kids becoming friends with cops with guns a head scratching one. Friendship and respect are different.

And the entry of cops into civic services and familial life in a role that is not directly related to solving crimes amplifies an inequality of resources that already exists in our neighborhoods: in rich (and largely white) neighborhoods, kids participate in civilian-run Little Leagues and soccer leagues. In poor (almost entirely Black and Brown) neighborhoods, cops run the community center and play basketball with kids, with all the complications that entails. As one police commander described it to me, he had become the unofficial "mayor" of the precinct he ran, with neighborhood residents coming to him for help in turning their water on and figuring out where to resolve food-stamp problems, among many other civic issues.

This messy entry into the civic sphere has an express and worthy motivation: the building of trust with the neighborhoods the police are tasked with protecting. Without trust, residents don't come forward as witnesses or serve as jurors. And without trust, residents become skeptical of evidence offered in court, further eroding the legitimacy of the justice system.

Police are a crucial civic service. And while they must, of course, be at the table, they should not run the table.

But there is a more direct line between police activity and neighborhood trust that does not also raise complicated questions of democracy, force and trust: for police to perform their core functions at a high level of excellence and to explain to the public what they are doing.

In January 2022, the NYPD did just this. A 17-year-old girl, working part-time at an uptown Burger King, was gunned down by a masked man, identifiable only by a wire connected to his earbuds hanging from his pocket. Four days later, the NYPD chief of detectives, an able and experienced commander, held a press conference to announce the arrest of the murderer and to explain the extraordinary, painstaking, round-the-clock work of his detectives to find the man. The chief walked through the steps of investigation without preening or self-regard. The facts spoke for themselves.

He did not ask for praise, though much was due. In that moment, he inspired a kind of deep trust for the skill and dedication of the detectives. No basketball game can do this. He showed what it means for the police to do their jobs at the highest level of excellence. At a time when clearance rates (the rate at which crimes are solved) in the city have sunk to depressing lows, this seems the most direct route to both a safer city and greater trust between the police and New Yorkers.

This singular focus on solving crimes would also go a long way to righting the oddly topsy-turvy world in which we now find ourselves and to increasing safety and strengthening our democracy. Police are a crucial civic service. And while they must, of course, be at the table, they should not run the table. That is the job of the mayor and his civilian deputies who have the panoramic view to assess what mix of civic services will keep New Yorkers safe and thriving.

Perhaps those civilian agencies, in turn, might take note of the principles Maple famously scribbled on a napkin long ago, and adapt them to government operations more broadly. Accurate, timely intelligence. Rapid deployment. Effective tactics. Relentless follow-up.