An excerpt from "Back from the Brink: Inside the NYPD and New York City's Extraordinary 1990s Crime Drop"

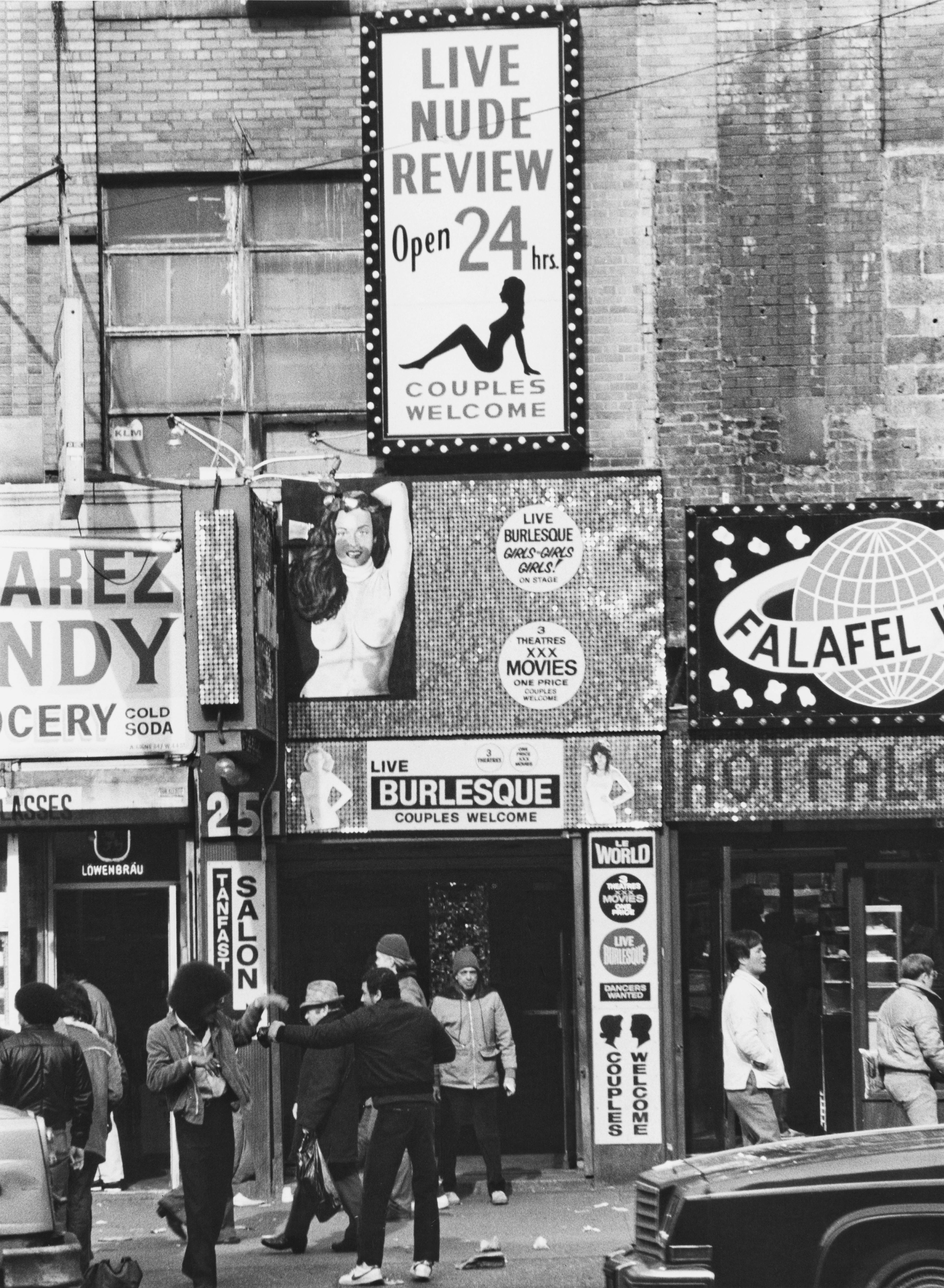

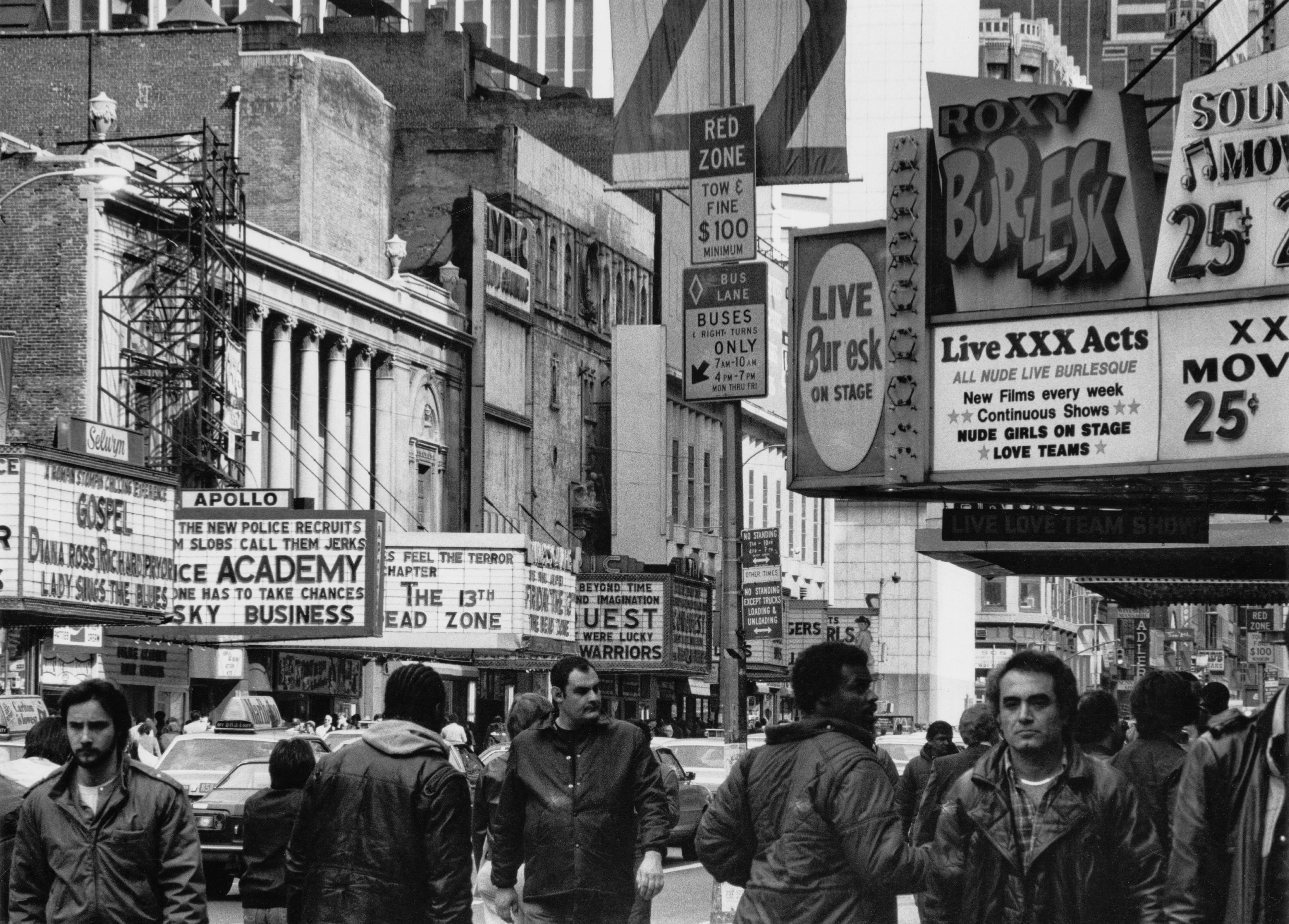

In 1981, Rolling Stone dubbed 42nd Street between Times Square and Port Authority Bus Terminal the "sleaziest block in America." The city's decline could be seen all along 42nd Street. From Grand Central Terminal to Bryant Park to Times Square to Port Authority Bus Terminal — despite a heavy police presence — beggars, drug addicts, hustlers, pimps, prostitutes, con artists and legitimate stores relieved visitors of their cash by request, guile or force.

Midtown Manhattan is unique in New York City in that it has deep-pocketed constituents with the financial means to invest in the area's well-being. At a time when Bryant Park was considered by many to be a lost cause, the Rockefellers helped establish the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation in 1980, which became a business improvement district (BID) in 1986, soon after Albany permitted neighborhoods to establish business improvement districts. The Times Square BID began operations soon after, in 1992.

That same year, Bryant Park re-opened to public and critical acclaim. The city’s crime drop had not yet happened, but the redesign of Bryant Park was a significant achievement in utilizing a broken windows philosophy to reclaim public space by reducing disorder, crime and public fear.

The improvements on 42nd Street and in Times Square laid the foundation for the New York City crime drop.

In this same era, between 1991 and 1993, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey embarked on its own ambitious plan to improve safety and the overall aesthetics of its gigantic bus terminal. Operation Alternative, which was a part of a greater "comprehensive improvement plan," reduced crime and disorder and improved conditions for hundreds of people living in the bus terminal and thousands of daily commuters.

Collectively, the improvements on 42nd Street and in Times Square — the reclamation of public space and the decrease in crime, fear and disorder — showed both that disorder could be fixed and that there was something in city life worth saving. These changes laid the foundation for the New York City crime drop.

Louis Anemone, New York Police Department: In 1978, headquarters wanted the junkies collared. They wanted the junkies moved. They wanted the prostitutes moved, particularly in Bryant Park. The park was a place where you'd send a minimum of two officers on the four-to-twelve and two officers on the day tour to work the park. The problem was, the officers were making low-level arrests, for sale and possession of marijuana and now you'd lose the coverage for the officer in the park. The bad guys would see the cops leave with an arrest and that would signal the “all clear” for mayhem. Forty-second street, the Theater District, Grand Central, Bryant Park, Madison Square Garden, Penn Station were the other key spots, and of course the Port Authority Bus Terminal.

John Timoney, New York Police Department: In 1985 or 1986, we had a horrible drug problem by Bryant Park. The drug dealers plied their trade there, and I was going to clean it up. It was disgraceful what’s going on there. It had gotten completely out of hand. Right around noon time, I’m going to make a statement. I had the Narcotics Division respond with a bunch of cops, and I kind of sealed off the entire plaza. We wouldn’t let anybody out, and we locked up all these people. Meanwhile, the New York Times was a block away taking pictures as I rousted all the junkies and drug dealers. I get the phone call and they started screaming at me, “Timoney, what the hell are you doing? Everybody’s upset! You’re suspending the Constitution!” So what are you going to do? (John Timoney passed away in 2016. This is an excerpt from an interview conducted by Jeffery Kroessler for John Jay College’s “Justice in New York” project.)

Daniel Biederman, Bryant Park Restoration Corporation: I started at Bryant Park in 1980. The park was horrendous in the early '80s. The Rockefellers wanted it fixed up once and for all. They were appalled at how bad it was. The purse snatchings around Grand Central Terminal then were truly scary. You had these amoral kids who would go up to a woman, put their hand on her chest, take her necklace, rip it off, or take her purse and run down the street with her clinging onto the strap sometimes, screaming. And there were kids doing twenty of those a week. That stuff stopped happening when the people who did it were imprisoned, and that was tremendous. Then, as to the other side of broken windows, which is somebody misbehaving, the concept of the cop on the street with a nightstick saying, "Hey, you guys are out of control. Tone it down there."

It was hard at the beginning because nobody believed Bryant Park could ever be anything. And all the biggest real estate owners in New York were really skeptical. What made me finally think it was possible was an article in The Atlantic. I brought up three copies to a mountain climbing trip I was doing in New Hampshire. I have The Atlantic in my backpack, all by myself in the woods with mosquitoes and time to read it. On the front is "Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety," by (George) Kelling and (James Q.) Wilson. When my wife picked me up, I said, “I just read something so incredible and so on-target for New York City.”

The key elements that made Bryant Park work and sustained it to this date were: one, getting it away from the city. Two is programming. Three is broken-windows policing. Four is the importance of softscape rather than hardscape—so that's plants and trees and lawn all being beautifully tended. Five is having enough money by paying attention to earned income, which almost no nonprofits in the city ever do.

That's always been my conceit about Bryant Park: high standards. That's why the restrooms have to be exquisite. Cities always say there's not enough money, but it's a matter of how you spend it. Governments too often have low standards, and they use as their excuse that there's not enough money to have high standards.

Let me tell you what I told the security chief who then passed it on to his guys. There are seven things I don't want going on here. This is my version of broken windows. Nobody can play loud radios, remember people with boomboxes on their shoulder? One, no loud radios here. Two is no spitting. A lot of people spit. Three is no cursing. I'm really tired of the language here. Four is no abusing women as they walk by. Five is no smoking, once no smoking in parks came along. It's been very good for cleanliness, by the way. And then things like marijuana smoking. When people come in and smoke marijuana, we throw them out or say, "You got to stop right now. No smoking in here." Same thing with cigarettes, same thing with cigars. But if the park smelled of marijuana, that would be the end of its good reputation. Sixth is no feeding the pigeons, which is terrible for parks because that brings rats when the bread gets left around. Seventh thing was people stupidly put their kids on top of the balustrades in the park where they could fall over and crack their heads. So we say there's going to be no more of that.

Today, Bryant Park gets no full-time PD. Our security guards don't have peace-officer status. They don't carry guns. They don't have weapons of any kind. They call for backup by their supervisors, and they help because they're former PD guys. And then we get nice backup from PD when we really need it. Once in a while we got an officer assigned, but we don't really need them most of the time. Unless it's dastardly, nobody gets arrested ever.

I was getting criticized for trying to take the park over with the argument being, "Oh, he's just going to make it comfortable for white executives. They'll be the only ones welcome. He's going to sanitize the park," and whatever. And I said, “If I have to rely on white executives to populate Bryant Park, I'm in big trouble because there aren't enough of them to get the crowds that I want. I want thousands of people.” And it's been borne out, because the average income of people in Bryant Park is about $50,000 or $60,000 a year. We've tested it. These are people who don't have huge backyards. They don't have private clubs or golf clubs. They don't go to incredibly fancy restaurants. They don't fly off to Europe. So all of those things can be offered to them, if you pay enough attention, in a space that's totally free and everybody can use. The park is now viewed as completely safe.

They made it harder for offenders to find targets, and they made it easier for guardians to supervise.

Marcus Felson, Professor, Texas State University: Routine activity theory says that for a crime to happen, you need the convergence of three elements: offender, target, guardian. You remove one of those, you prevent the crime. "Victim" is the wrong concept. You have to separate the target from the victim. If I break into your house when you're not there, you're the victim, but you're not my target. I don't care who you are. I just want this stuff in your house, your money. And I realized that a guardian isn't a police officer, it's usually an ordinary citizen. I say "offender-target-guardian" literally. It is not a metaphor. And when I say convergence, I don't mean a convergence of ideas. I mean a physical convergence. Routine activity theory is déclassé because it's not intellectual enough. It's tangible and down-to-earth, and a fair number of intellectuals are downright insulted by it.

In terms of Port Authority, Ken Philmus, the manager, was transformative. He was thorough, and he would deliver. Philmus would say, ''Oh, but it wasn't me.'' He tried to minimize his centrality, and I think that's because he had a boss and doesn't have that big ego. He was a bit self-effacing, but he was clearly in charge. They removed targets and changed the convergences. They made it harder for offenders to find targets, and they made it easier for guardians to supervise. They changed the pedestrian flows and sightlines so people could see what was going on. They changed the entries and the visibility of the entries. It was basic situational prevention and environmental design that used routine activities implicitly. It was symbiotic, what happened outside the big building and inside. And the Times Square BID did make a difference for outside, and there's no way to tease those apart in a scientific sense.

Ken Philmus, Manager, Port Authority Bus Terminal: My job was not to deal with just the homeless problem but to deal with every aspect of the bus terminal that existed, put my arms around the whole thing and think about how we could make the whole place better. I remember distinctly going to the Bus Terminal at two in the morning to see what I was getting myself into. I said, “Oh, my God, what am I doing?” You'd walk into that bus terminal in 1991 and you'd have to step over bodies to buy your bus ticket. You'd see dead people. While some workers really were dedicated and cared, many had absorbed some of the personality of the building, and it was like a defeatist attitude, like we just can't deal with this.

It was just impossible to police. The police had very limited ability to do things because the main floors of the bus terminal were considered a public space. Our customers shouldn't have to deal with all the kinds of things. The folks would be living above bus gates in the areas where they could climb up and be warm in the winter and cold in the summer—heating and air conditioning. They'd get some crack, smoke it up, come down, rob a few people, buy some crack and go back up. People were living above your bus gate and something nasty would fall on your head as you were waiting for your bus. I mean, it was horrible.

It was really important that it was holistic and that it wasn't one thing at a time. I sat with the board of the Times Square BID and the Fashion Center BID because the Bus Terminal bordered both places. We worked with John Jay College. I talked to the people who ran SROs and other kinds of places that provided services. One program was for runaways. There was all kinds of pimps and pedophiles in the building looking for the young girls and boys coming off the buses from long distances. Police would have to catch them in the act of doing something, which became extremely difficult for the police to be able to accomplish, to actually have a case where the D.A. would take them to court. That's why the runaway squad was put together. We had a group of about four or five cops and two sergeants, if they saw a young person in the building that didn't look like they belong there, somebody that just got off the bus from Ohio and was wandering around, before they got picked up by a pimp or somebody else, they intervened. And it was an amazingly successful program.

I really tried to let the customer feel that we were in control, that somebody was controlling what was going on, that it wasn't like the Wild West.

One thing which I felt was incredibly important was cleaning up the building. The building was dirty. We were finding human excrement on the floor and crack vials and all that other kind of stuff. Part of the problem was that the cleaning people couldn't get machines in to clean the floors because people were lying on the floor. So we changed all the cleaning routines and the equipment that they had. I did little things at the start, I put barriers between the urinals, and you wouldn't be able to look into the one next door. What a little thing that was. We painted the bathrooms and improved the light and improved the ventilation so that it wouldn't smell when you went in.

I really tried to let the customer feel that we were in control, that somebody was controlling what was going on, that it wasn't like the Wild West. And that worked, it really did work. When the panhandling law changed—that made all the difference—we could start Operation Alternative. It's always difficult between civilian management and police management and civilians and police. If we're going to ask police to do this civilian-oriented approach—which they were totally unused to, trying to cajole homeless to go with the shelters as opposed to kicking people out or arresting them—we need to provide incentives. There was more overtime, but it was necessary.

Jeff Marshall, Port Authority Police Office: What came along was this Operation Alternative. I didn't think it was working in the beginning, no, but as it went on, you could see the change. That's absolutely, absolutely when it changed. They basically told us, "You are to offer assistance to the homeless people. And if they don't accept it, you will remove them from the premises. If they want assistance, you take them to the office, the Operation Alternative office." There were social workers down there that would provide these people with a bed to stay that night and some sort of social services that were put in place.

We had to do sweeps in a staircase. You'd start from the top, you go in with three officers plus a supervisor, and you just walk the staircase from top to bottom. Just telling everybody, rousting everybody, getting them out of the building, get 'em out of the staircase. Just to let them know they're not welcome there anymore, and that there's a thing in place for them to get services. It was a daily routine. You'd do all the staircases that day. And you'd kick 'em out. But you'd always offer them the services, for them to go someplace. And if they didn't elect the services and didn't want to leave, that's when you placed them under arrest for trespassing, and you'd put them into the system.

And they fixed the doors, they being the Port Authority. They locked the emergency exit doors so you couldn't get in from the outside. They did things correctly, what they were supposed to do. Lights were out? They fixed the lighting. You know you had (Commissioner Bill) Bratton that came along in Transit, and eventually the Port Authority got on board and established their own rules and regulations. So in '91 they designated certain areas that only ticketed passengers could be. Basically the do's and don'ts of what you can do inside the bus terminal. You can't sit here. You can't do this. You can't do that. Only ticketed passengers are allowed beyond this point. So once they had those regulations in place, now we had something that the officers can use as a tool to basically remove these people, because now they're trespassing.

But it wasn't like everybody was getting arrested. There were services that were in place at that time, and that's part of the reason why it made it. Part of this Operation Alternative is that they would try to get them jobs and clean beds and a place to stay. Two of these guys were probably the first two guys that were hired to clean up 42nd Street. I think those first two guys eventually they became supervisors. They worked literally from the bottom up. These people started growing.

As a result of Operation Alternative, you got rid of the homeless people who are committing the crimes. You go into the broken windows theory. If there's one window broken and it goes unrepaired, soon you have all of the windows broken. It all worked together. First the subway with the graffiti and then with the turnstile jumping, and then the Port Authority. They all put it together. And the city also got on board when they started cleaning up 42nd Street and Times Square. Because that's really what we're talking about.

Gretchen Dykstra, Times Square Business Improvement District: I was the founding president and CEO of the Times Square Business Improvement District, now known as the Times Square Alliance. Arthur Sulzberger Jr. from the New York Times was behind the establishment of the BID. Arthur had realized that the Times had an issue because people were turning down jobs at the New York Times because they did not want to work in Times Square. He had a problem. The state law that allows BIDs says that to establish one you must have more than 50 percent of the property owners approving the BID. It puts a tax on property owners, and therefore can put a lien on their property if they don't pay it. Arthur thought 50 percent was too low of a bar. So he and his other Times Square colleagues worked until I think we had more than 95 percent approval from the property owners. He had lots of support from the theater owners and the hotels and the restaurants.

We officially began operations on January 1, 1992, and I was there until the end of 1998. So I was in the hot seat for those key years in the '90s. We had a $6.5 million budget to cover the blocks from 41st to 52nd, from the west side of 8th Avenue to the east side of 6th Avenue. The theaters were doing so-so with international ticket holders, but nobody else. Hotels stood empty, office buildings were bankrupt. Three new office towers stood empty. They were either bankrupt or they hadn't been able to fill and rent their space. Those included the Bertelsmann Building, the Morgan Stanley Building and the iconic One Times Square. We were working for 500 property owners in Times Square, but because Times Square is the crossroads of the world, we were also working for the public. We had 50 public safety officers and 55 sanitation workers. Eventually we had homeless outreach and special events and a press office. We had a simple mandate, to make Times Square clean, safe and friendly.

Times Square was filthy and rundown. It was grungy, not scary, just unpleasant. I remember 8th Avenue being rough around the edges and a little intimidating. But the heart of Times Square? I was struck by how empty it was. Now even when I say it was empty, the number of people going through Times Square was in the tens of thousands. The tourists were still coming in to see the signs, but they were nervous when they came. Once you left the heart of Times Square, the "bow tie," those streets were really dark if there wasn't a theater there. We were opposed to floating bonds because it comes out of the city's full bonding authority, but we took some of our dollars and installed new lighting on all the side streets.

The perception of crime far outstripped the reality, but the reality was constant and pervasive.

There was no doubt that the perception of a violent Times Square was overstated, but that's what happens. A large part of this was telling people that Times Square was getting better, and we were relentless in telling the world. We did it in a whole slew of ways. We opened a security booth at 50th and Broadway and ended up on David Letterman's show when he came down and interviewed the guy sitting in the booth. That stuff mattered. We had to convince people that it was okay to return. We will be there for you.

The perception of crime far outstripped the reality, but the reality was constant and pervasive. It was pickpocketing. It was small time drug dealing. It was three-card monte which turns into pickpocketing. It was runaway kids in Port Authority. I was very aware of Operation Alternative at the Bus Terminal, and I think it did a good job. In fact some of my colleagues went on tours with them. The Port Authority was interested in people who were coming off the buses. My basic constituents were concerned about homeless people who were living in Times Square, permanently living there, not passing through. We did a count and identified 33 people who made a permanent home in Times Square.

To change that perception of an unattended neighborhood, we decided to dress our public safety officers—who were not allowed to make arrests—like police officers. A large part of it was to make sure that they could be seen, and that they were helpful to people who were nervous about the neighborhood. We didn't want to hire people who wanted to be cops. We wanted people who wanted to be community people. But we knew that we could only be as good as the cops and agencies that were backing us up. We were truly supplemental to city services, to help them as opposed to beating up on them. Police were key to what we were doing. The cop standing on the beat had to be responding. Police, sanitation, DOT and the BID worked really well together.

One satisfying fact is just the complaints that Times Square now is too crowded. A lot of people think Disney was the turning point, but more so Bertelsmann was. They bought the building at 45th and 46th and when they put Virgin Records in the ground floor and basement in 1996, they were open past midnight! That was huge. This really made a difference. I don't think Times Square had been "Disneyfied." I always rejected the term "Disneyfied" for a host of reasons. I think that Times Square is back. There is a tendency to romanticize the gutter, and I don't think that there's any upside to that.