Connecting people and neighborhoods by design

“Roman garbage” were about the first words I ever heard Jeanne Gang utter. We were sitting in a grand McKim, Mead & White building that has been home to numerous New York City municipal agencies since its construction. Or rather, we were sitting in the ruins of a grand building, now fitted with dropped ceilings and buzzing fluorescent lights and decorated in the Early Stacked Box style favored in many government offices. At that time, Gang was already a dazzlingly accomplished architect, a reputation that has only snowballed since then. A MacArthur Fellow and one of the most influential people in the world, per Time magazine in 2019, she has projects across the country and around the world. Her ideas have been exhibited widely, including at the Museum of Modern Art and the Venice Architecture Biennale.

On that day, though, among the boxes, she was there to talk through a “neighborhood activation” project with some of the residents of the neighborhood. Unusually for an architect, but not for the way in which Gang envisions “making architecture,” she initiates projects that have no client but can spark creativity and innovation. She sees architecture as a way to spur social change. She and her team were working with residents in two New York City neighborhoods to realize the residents’ improvement ideas, both small (additional lighting) and large (rehabbing a library as a neighborhood anchor, changing when and where services were delivered). Sitting side by side, neighbors spoke as the architects sketched the thoughts and made them come to life.

For Gang, architecture and design are crucial creators of social bonds. How a building is designed and how it lives in a neighborhood, how accessible and literally transparent it is, can bring people together or pull them apart. Roads and power plants may be the first things people imagine when they think “infrastructure,” but infrastructure is more than that: It is the human connection that libraries, community centers and more can engender. And neighborhood activation, she has noted, is the process that recognizes the spatial and relational way people are tied to each other and to a common future. It is a process that implements a vision to improve safety block by block, led by people who are linked to the place and to one another.

This large frame of ecology through which Gang views the world extends to bureaucracy and governance as well. Gang is a pragmatist in figuring out how to make projects go. That requires uniting many actors — residents, government agencies, neighborhood groups — around a common goal. And architects can play an important role here.

Oh, and the garbage? I never did find out whether it was Etruscan trash or modern disposal that had caught her eye. But the inquiry is just one of many reflections of her relentless curiosity and creativity, her sense of the messy interconnectedness of the man-made sphere and the natural one, all adding up to the inexorable drive to make the world a better place.

I caught up with her last month to learn more about the progress of her work. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Elizabeth Glazer: A lot of people think about architecture as a static exercise: An architect designs and builds a building. But looking at your work, it feels so different. You synthesize so many different currents, historical and political, environmental, human. You’ve sometimes referred to this idea of “actionable idealism.” What is that, and how has it played out?

Jeanne Gang: Thank you for noticing the work in that way, because those are the things that tie it together. We work with many different building types, in different kinds of cities and neighborhoods, at different scales, and in very different climates. So innately, every project has its characteristics. To me, it seems right and natural to work with those specific criteria to create the design, as opposed to applying the same style to every project, like a veneer that makes it look the same on the outside. We want to understand the particular people, issues and environment involved — so we can use design to strengthen and improve the relationships between them.

Architecture can be a catalyst to help transform things, to make positive change.

The term “actionable idealism” came about because I was trying to describe the intention behind our practice. Architecture can be a catalyst to help transform things, to make positive change. I believe that. I’ve seen it. Our studio is motivated to find the right projects that can move the needle on the big issues we care about — that’s the “idealism” part — through taking real actions toward accomplishing them. These can be more traditional architecture projects that are commissioned by clients. But we also initiate our own projects, from research and ongoing experiments to urban design, writing and exhibitions.

In terms of specific projects, oftentimes I think of our work on the Chicago River. Back in 2011, we started collaborating with the Natural Resources Defense Council to think of ways that we could make Chicagoans aware of pending legislation that would require the municipality to clean sewage water before discharging it into the river. We wanted to help people understand why this was so important to the health of the waterway and the whole region — not just environmentally but also economically — and how it was related to a range of water issues, including invasive species, flooding and poor water quality. We realized that one key step was making sure that people were aware that there is a Chicago River in the first place! It has been used as a private industrial channel for so long that many people didn’t think of it as a public space or natural resource. We ended up self-publishing a book about our research and our vision for the river’s future, “Reverse Effect,” which was shared with people across Chicago. We wanted it to inspire them to become stewards of the river and active in improving its conditions. The book reached the mayor, and we ended up being commissioned to design two public boathouses, one on the North Branch and one on the South Branch, that opened in 2013 and 2016. They’re one architectural solution to bring people to the river, youth especially, to enjoy it as a public asset and foster stewardship and momentum for its revitalization.

Fast-forward over 10 years, and you would not believe the transformation of the Chicago River! I’m not saying that our book or little boathouses did it alone, but they did contribute to a renewed dialogue about the river and what it could become next. I think that’s what I’m so interested in — there’s just something about architecture that makes people feel excited and engaged. In a community that hasn’t had a lot of investment, for example, a new building or a renovated older building can really get people rallied around a place: to be proud of their place and have it work for them. That’s why I think you can do urban design on its own, but it doesn’t have that spark until it gets the architecture to go with it.

EG: There’s something about the physical presence of a building and the participation in it that feels immediate and real, compared with social programs, which can take forever and are invisible maybe. Your Civic Commons work is so interesting in that regard. Whether it’s the Chicago work or the New York City work or other things, how do you engage with the community? What are your ideas about making neighborhoods work?

JG: That’s where this aspect of engagement comes into play. We’ve been working on adapting our process over the years to engage more community members, to have them as partners and to have them at the table during every phase of the design process. Really finding ways to get their input and, ideally, empowering them in the process.

The result of that engagement, in my view, is that projects are more fully adopted by their communities because they’re co-created in a way. It’s a long process, but it’s a valuable one that will make the project have a higher likelihood of success because it will be what people wanted — they will embrace it and make it their own.

EG: Literally, you’re sitting down with residents at a table, drawing what their ideas are and working with them?

JG: Those sketching-together moments are only one part of it, though that’s a really exciting part because you’re trying to hear what people are saying and convert it into something that looks like a place.

So we draw things, and it’s a way of talking.

EG: You’ve talked about interiors and how they connect people and might draw people in. I was thinking about that recently because a book has come out about Rikers. And there’s this one incredibly compelling part in which somebody who was imprisoned at Rikers says it really didn’t feel all that different from the poor neighborhood they came from, from what the city housing projects looked like and from what his schools looked like. I’m wondering, when you think about public buildings and how people get connected, how do you inject a different spirit or design?

JG: That’s so interesting, that observation. It says a lot about the process we normally use to design buildings, and also about the era during which many institutional buildings were constructed and how they can feel. From a sustainability standpoint, it’s great to conserve as much of the existing built fabric as we can, because it represents so much embodied carbon. A major focus of my research over the last few years has been on adapting existing buildings to keep that carbon from being wasted, which is what happens when you tear everything down and start over. Regarding interiors, there are ways to ameliorate some of these negative aspects of existing public buildings — to change the feeling of the interior. They’re places where we want social interaction to happen, and ultimately where we want social cohesion among neighbors to arise. It’s a combination of programming and design, whether it separates people or brings them together, that can make the greatest impact.

If you can bring people together, that’s the right place to start. The principle behind it is what Mindy Fullilove and other sociologists call the strength of weak ties — those bonds that are created gradually by shared sight lines or by using places at the same time, like food preparation areas or community spaces, where you can see other people and face them. These are the kind of spaces that start to psychologically bring people together.

You also have to give people choice in interiors, so they can decide if they want to be part of the edges of the space or if they want to be on center stage. It’s like theater, in a certain way. What are the types of contact that you want to support and what are the ones that need privacy? Those are some of the questions that we try to get at when we speak with people about designing a community space.

EG: So it’s the inside, and it’s also how the aspect of the building, its placement, the roads, the street furniture, how a neighborhood can be divided or united by design …

JG: Yes, absolutely. You can see that, for example, in the project we worked on together in Morrisania, the Bronx. Their neighborhood has steep topography, with a set of urban stairways that are supposed to function as connectors, but the stairs also had negative connotations for the people who live there, mainly because they’re dark and uninviting. People wanted to use this connection, but the physical aspects of the space were not encouraging it.

So we worked closely with the local community to understand what was needed there. It was simply having some lighting, having some art — local art, that people feel connected to and feel connected to the artists. Things like food carts and other simple elements, even if they’re temporary, can really help a space transform.

EG: That Morrisania project was really a dazzling transformation, the before and after of the deserted steps, and then the brilliantly, colorfully lit lively life that was supported afterward.

JG: Yes, it’s great to see people adopt something like that. And in that case, as a designer, our role was just identifying what it could be. It was others in the city, and local community members and organizations, who helped implement these ideas.

We need urban ecologists running projects to create habitats that are beneficial to all of us.

EG: You once said to me that if you think about a city, anywhere from 50% to 90% of it is actually owned by the government, whether it’s roads or housing or libraries or fire stations, and at any one time there are a gazillion capital projects going on, and they’re an opportunity to think in a different way about the cityscape. Could you talk about these opportunities — and the challenges?

JG: The challenges are obvious. It’s the silos, the different budgets, the different staff who are forced into competing for resources. What we do in our office is form teams around specific projects. The teams have different expertise, but they’re porous to the studio as a whole, and team members will eventually move between projects, creating new combinations of people and fresh collaborations.

It’s a completely different setup than a typical bureaucracy, which comes out of the industrial revolution and the modern notion of separating things into their specific characteristics. Our way of working and thinking is more similar to the field of ecology, where it’s less about separating different species and more about how they interact with one another and their environment. That’s the approach we need for our cities. We need urban ecologists running projects to create habitats that are beneficial to all of us.

EG: You’ve talked about that, both in connection with some very famous buildings that you’ve built, for example, the Aqua building in Chicago, where people can see one another from floor to floor, and also in your work within cities. That does seem to be at the heart of everything, that human connection.

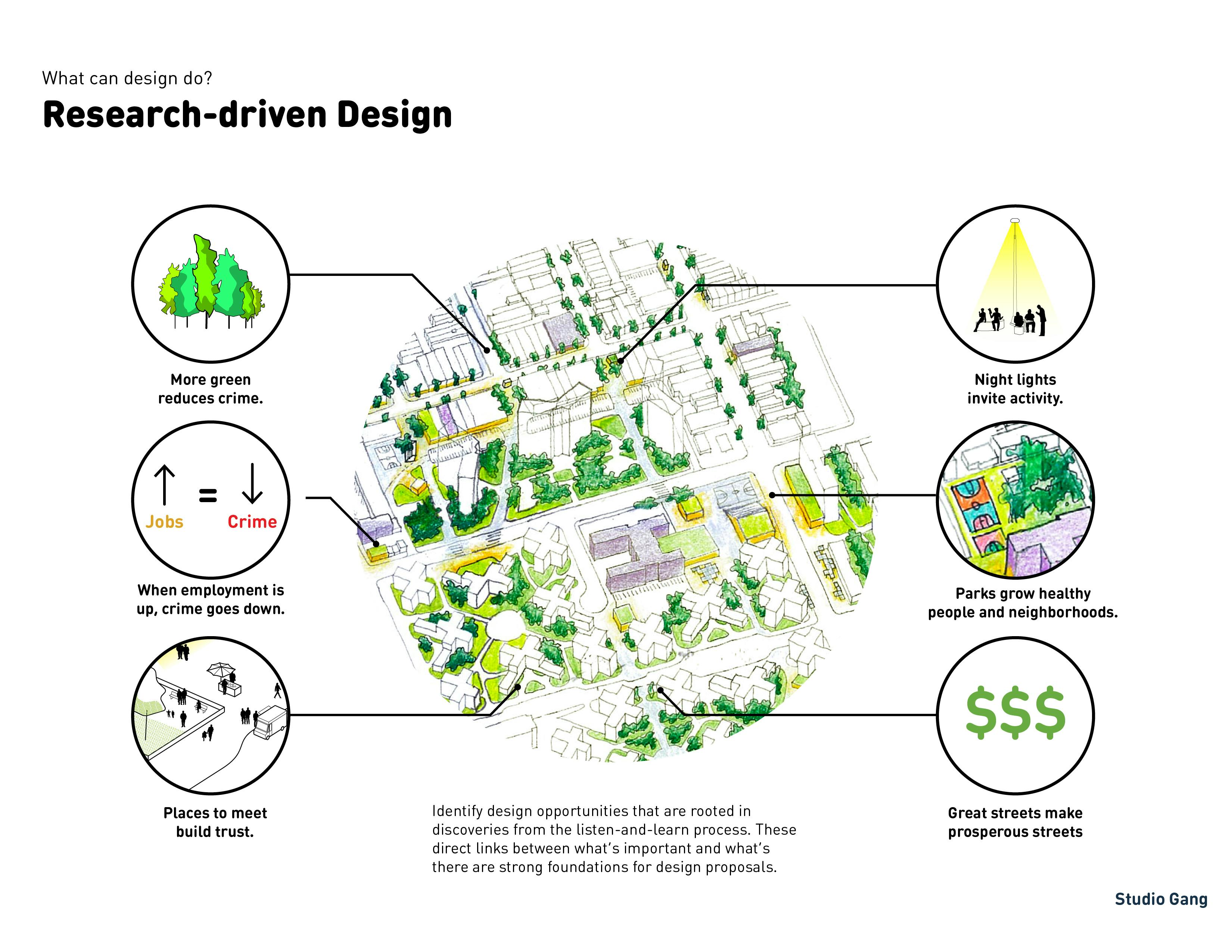

We worked with the community to learn about their neighborhood and start imagining how we could build on existing assets — a school, a library, even a vacant lot — to start to connect these places, invest in the community and foster greater public safety.

JG: Our work is architectural, but it is also urban. For our urban projects, we’re mostly focused on working in neighborhoods, with communities, to better connect and amplify their existing assets. You learn what people care about, what they like and don’t like, and what their ideas are, as well as about the programs and physical spaces that already exist. The motto is “Start with what’s there.” What is good? What can we build on? We don’t want to start from scratch, to drop a project into a neighborhood and just hope it works.

EG: Do you have a particular example in your head as you describe this?

JG: One of the most recent was our Neighborhood Activation project in Chicago, where we were working in the West Garfield Park neighborhood. This is a part of the city that experiences a lot of gun violence, but there are also a lot of positive things happening here. In partnership with two nonprofits, the Goldin Institute and the Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative, we worked with the community to learn about their neighborhood and start imagining how we could build on existing assets — a school, a library, even a vacant lot — to start to connect these places, invest in the community and foster greater public safety. The realized project that came out of that process was really interesting and unexpected. An idea that came from the community was to build a temporary roller rink on a parking lot.

I remember roller rinks from when I was a teenager — evidently, they’re back in! It was a very easy-to-pull-off transformation of an open space. A few residents were worried that it would be dangerous, but most people felt that bringing more people together in the public realm is what would make the area safer. And it got done. Mayor Lori Lightfoot here in Chicago really prioritized the project, and it became beloved by the community. It opened very quickly. There are additional ideas in our proposal that have yet to be realized — the medium-term and long-term projects — that are designed to knit the roller rink and surrounding community plaza with other assets in the neighborhood.

EG: You’ve been such a prime mover in the neighborhood activation idea and how architects can play such an important role. Government could also. How do you see something like neighborhood activation being institutionalized?

JG: I can be critical of my own profession because we don’t really learn much in school about how to work with communities. When I started my practice, my first projects were community centers in Chicago. I really loved getting to know the different groups and working with them to create a place for them to come together. They call Chicago a city of neighborhoods. The ethnicities and racial makeup of neighborhoods change over time, but people tend to stay in clusters. On the bad side, this creates or deepens divisions, but on the good side, it allows communities to thrive together.

Through these projects I got to know the Chinese American community, a community of foster care families in Auburn Gresham, the community in North Lawndale. In addition to working with different people, learning how to listen and collaborate, I also gained an understanding of the community center typology that I’ve brought forward into other projects. How can a museum, for example, function more like a community center? So for various reasons, I think this is very valuable training for architects to have. But as for getting it into the drinking water, it is a lot of time and it’s a lot of commitment, and we need to have good examples that will illustrate that it works.

To get back to actionable idealism, sometimes projects are sparked that are more experimental, because we see something that’s so disturbing in the news and ask ourselves, How can this be happening? With police brutality, for example, back in 2014 when Michael Brown was killed. That motivated a self-initiated project looking critically at police stations. Instead of investing in them as fortresses, we explored what could happen if we invested in them as community centers.

As public buildings, they belong to all of us, and we thought they should be supporting community safety and services more broadly: mental health, education, recreation and physical health. We did a lot of interviews and workshops as part of the project, with community members, police, experts, policymakers and local organizations. We also used the report of President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which contained six pillars to improve community policing. We tried translating the ideas we’d heard in the engagement sessions and the policies from the report into physical space, as a way of trying to figure out if architecture could help address police brutality in any kind of meaningful way.

What ended up happening was that we realized the issue was so much bigger than architecture. A small built project did come out of it, a recreation space built on a former parking lot — so full circle to the roller rink, in a way. Looking back on it, I see the difference in perspective and understanding that almost 10 years makes. But our desire continues to try to address big issues through using what we know how to do, which is design in service of community, in service of civic space and better, stronger communities, more resilient communities.

EG: That project foreshadowed a lot of the things that came out of the protests following George Floyd’s murder, and a lot of the things that you and your team heard had to do with that trauma and a conflicted view of police. Could you have a snack bar in the police station? Do you actually want to go in?

JG: Right. No one wanted to go in. And it tells you something. It’s not thought of as a place for a community. But we own these buildings too, we, the public. They should be serving us, and we should be investing, not just in the station. The investment needs to be in housing; it needs to be in recreation spaces; it needs to support street improvement projects and health services.

EG: At Vital City, we’ve started this project called Vital Signs. Initially, we started with indicators of what’s going on in the criminal justice system, but we want it to be also indicators of a functioning city. What do you think would be great measures of the vitality and well-being of a neighborhood or a city?

JG: That’s a great question. One key indicator is when people act together to change something. I always look for gardening in public plots. If you see people taking over a place, they’re doing it because they care about it and they’re caring for it. That’s a really clear sign that we saw in Brownsville and Morrisania, for example: There were many gardens that were self-initiated. You don’t do that unless you feel some attachment to that place. Voting is also so key to being engaged. If you could see by neighborhood block if people are voting, then that means they believe they have agency to change things.

We also have to design spaces that are a little bit flexible. For example, a place like the South Pond at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, which was pretty run-down before we were commissioned to put in a new boardwalk and pavilion. The pavilion became a kind of magnet. People started to adopt it, hosting community classes like yoga, using it as a dance stage, or holding an impromptu wedding — all sorts of unofficial things. When we go back to our projects to see if they are successful, one of the things we look for is new programs that we didn’t expect. It shows us how to build in a certain level of flexibility, so the places we make can be adapted and not just used for the original intention.