Another approach can make a difference.

What makes people and places safe, more than force, are the million and one connections that bind us together in an unspoken set of understandings and informal rules.

In 1994, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) committed an act of staggering courage. With murders hitting an annual high of about 2,000 for the fourth year in a row—a peak not seen before or since—the NYPD declared that it would be responsible for controlling crime.

This seemed a foolhardy claim at the time: the conventional wisdom was that the police could no more control crime than a New Yorker could will the rain to fall. After all, causes of crime are complicated and, in many cases, little understood. Police power is limited and, by its nature, mostly exercised after the harm has occurred.

But the NYPD's bold stance in the early 1990s was a game changer that would be emulated by police departments across the country and around the world. Instead of simply patrolling, investigating and arresting, the police began to analyze the drivers of crime. And, through a regular department-wide meeting called CompStat, it began to look for ways that largely siloed groups within the department—officers on patrol, detectives, narco-teams—could share information to solve crimes.

Although experts still dispute why crime declined over the past 30 years, the evidence is clear that policing mattered. NYPD's daring move to hold itself responsible for reducing crime drove a number of basic management improvements in a system that wasn't exactly known for good governance: organizing around a goal, mobilizing resources towards that goal and measuring the results. It was a galvanizing change for police.

Today, after three decades of sustained reductions in crime, expecting the police to reduce crime no longer seems remarkable. Despite the now-acknowledged harms that have come from the default to the criminal justice system—among them the eviscerating effect of the overweening use of incarceration—for better and for worse, when crime ticks up, all eyes turn first to the police. Recently, as shootings in New York City doubled from their 2017–19 lows—part of a nationwide spike in gun violence—this impulse has been on full display. Just three weeks into his tenure as mayor, Eric Adams announced a blueprint for addressing gun violence that reflected his philosophy that "intervention," meaning police, comes first, and "prevention," meaning services and programs, comes second.

Shortly afterward, President Biden visited the city to announce his intention to deploy federal prosecutors and law enforcement agencies to target gun crimes, a muscular move and an eerie echo of President Clinton's 1994 mobilization of federal prosecutors in an area that is traditionally the province of local law enforcement.

There is, however, a completely different and powerful way to reduce crime without the costs that have come along with our heavy reliance on the criminal justice system. We have used it virtually not at all in any systematic, organized or intentional way. What makes people and places safe, more than force, are the million and one connections that bind us together in an unspoken set of understandings and informal rules. The expectations of our families and our neighbors—their approval and disapproval—checks our behavior. This is what social scientists call informal social controls. And if we didn't already know it from our own experience, researchers have documented that these connections, and the organic rules of behavior that spring from them, are what make thriving neighborhoods. A web of institutions help reinforce these norms. Neighborhood organizations—the kind of civic associations that Alexis de Tocqueville noted back in the 19th century America excels at—play a key role in helping to knit together our social fabric. The sociologist Patrick Sharkey has demonstrated that the presence of these kinds of institutions is directly connected to fewer murders.

The dynamics of informal influences may seem inchoate and difficult to deploy. But they are not. We have learned a lot about the specific programs, skills and physical improvements that can help neighborhoods thrive. For example, environment matters a lot: lighting in a housing development reduces nighttime felony crime by 36 percent and greening lots reduces violent crime by 40 percent. So do employment and educational opportunities: jobs for youth can reduce violent crime arrests by 30–45 percent, and improving the quality of schools can decrease crime by half among the highest-risk youth. These actions have an immediate effect (and long-lasting benefits), but operate from a different premise—strengthening the social fabric, which creates its own virtuous cycle.

New York City provides some evidence that when a more precise and limited use of police is combined with sustained investment in community organizations and civic services, the balance can produce safety. For three years, from 2017–2019, the city experienced the lowest crime and incarceration rates in recent memory. A few things came together to make this possible: the police made some considered decisions about what kinds of conduct merited arrest, resulting in a 50 percent drop in arrests, mainly misdemeanors. In a similar vein, local prosecutors and judges began to rethink their approach, relying on the evidence that community-based programs instead of jail could keep crime low.

The changes weren't just happening within the justice system. In a number of communities, "violence interrupters"—local residents with direct experience in the justice system who were trained to mediate disputes—cooled tensions before they erupted into gunfire. In these communities, shootings dropped by 30 percent, with one area going for more than a year without a shooting. City government exponentially expanded funding to provide support through a new Office of Neighborhood Safety that also incubated new ideas. One of those, taking a page from NYPD's CompStat, was the Mayor's Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety, which implemented a series of resident-led NeighborhoodStats to bring together local residents and city agencies to identify and address the conditions that incubate crime. The solutions included a universal summer youth employment program. An evaluation showed that crime fell more in MAP developments than non-MAP developments—in five years of MAP, index crime fell in participating communities by 7.5 percent, compared to 3.8 percent for non-participating developments.

These efforts were not fully formed, fully funded or close to perfect. Nor were they coordinated with rigor. They did not, in any meaningful sense, constitute a "system." But they were—and still are—the beginnings of a balanced approach to public safety. This "social fabric" strategy offers a way that is immediate, deployable and visible. And because it is based on participation not coercion, it offers the benefits of stable lives without some of the harms of interrupted life courses that are endemic to a system based on force.

Examples of civic goods that reduce violenceRaising school drop-out age to 18Lengthening the school dayGiving kids summer jobsCivilian supervision for kids on their way to/from schoolDriving curfews for young adultsImproving quality of schoolsSupplemental social/emotional programming in schoolsLead paint remediation in householdsReducing child maltreatmentMitigating post-divorce income shocks to households with childrenMitigating short term economic insecurityGeneral relief spendingShort term financial support to mitigate domestic violenceReducing access to alcoholIncreasing access to substance use programsMore effective mental health treatment optionsDrawing school district boundaries to reduce school socioeconomic segregationReducing foreclosures and foreclosure-induced vacanciesProviding affordable housingEliminating Stand Your Ground lawsAlternatives to felony prosecutionReducing juvenile incarcerationStarting/supporting business improvement districts

For links to studies and additional violence reduction interventions, see Anna Harvey's compilation.

The Lessons from the Blunderbuss Approach

While policing is also a civic service, it has never been deployed as part of a unified city strategy. That separation may explain, in part, why the galloping use of law enforcement has come to dominate how we think about safety.

In the years since 1993, the use of police as the primary antidote to crime led to a massive increase in the use of jails. One fact stands in for how profoundly this disrupted, and continues to disrupt, familial, neighborhood and economic stability: One third of Black men living in the city's poorest zip codes can expect to see the inside of a jail cell by age 38.

Stop-and-frisk became a synecdoche for a system gone haywire and a city that was out of ideas about how to maintain social order beyond the use of force. Street stops—a legitimate police function, sanctioned by the Supreme Court—spun out of control, jumping to almost 700,000 stops annually. For young Black men, daily life—the trip to the grocery store or the visit to the park—was all-too-frequently interrupted by an encounter with police. This kind of enforcement further corroded the already uneasy relationship between police and communities of color in New York City, chilling the active participation of residents in myriad ways, including coming forward as witnesses and serving as jurors. While stops have declined by 95 percent, a kind of phantom limb syndrome has resulted; in many of the neighborhoods that the NYPD historically targeted, there continues to be low levels of trust.

Over the past few years, police accretion of more and more civic functions has also sharpened the question: what is the role of local government—established to provide for the safety and well-being of all residents—and what is the role of the armed force that operates under its direction? In New York City, the police fund graffiti removal, run employment programs and operate community centers. Across a broad range of civic services, including mental health and homeless outreach, when deployed as part of a safety strategy, the police are not just at the table, they run the table. Today, we do not think twice that when the president comes to town to meet with the mayor about crime, they go meet the police commissioner at her headquarters; she does not come to them in the seat of the city's democracy and civic power, city hall.

All of these issues—the role of police, the trust of neighborhoods, the efficacy of civic life—collided as the pandemic hit.

A Profound Untethering

By mid-March of 2020, the city's streets were empty, the most prominent sound the blaring of sirens as ambulances rushed people to hospitals. All the normal rhythms of daily life—work, school, play, shopping for groceries, stopping in at the neighborhood diner or going to a concert—disintegrated as people isolated at home. With no one on the streets, violent crime fell to almost nothing.

In mid-May, all that changed. As the restrictions lifted, gun violence began a sharp rise. By the end of May, in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, protests against police brutality and racism swept across the United States and continued through the summer. New York City was no exception. Day after day, there were thousands of people in the streets. Videos of police roughing up protestors went viral and launched two investigations that produced damning reports about sanctioned police violence. And there were instances of looting around the city, particularly in the Bronx, midtown Manhattan and SoHo.

The criminal justice system seemed to be coming apart at the seams. As shootings soared, police withdrew from the streets, with gun arrests dropping from nearly 60 percent from May 2020 (376 arrests) to July 2020 (155 arrests). Aggravating the inability of the police to make cases was the further withdrawal of residents from participation as witnesses. By the summer of 2020, in the neighborhoods most affected by violence, the number of shooting cases that were successfully closed by the police dropped to approximately 30 percent. Courts, which were operating in a limited capacity and mainly remotely, began to stall. As a result, the number of people in jail swelled, from an all-time low of 3,800 to over 5,500.

Some profound untethering was at work.

Shifting the Center of Gravity

The startling rise in shootings sharpened a war over the degree to which a host of criminal justice reforms that sought to shrink the footprint of law enforcement and reduce the use of incarceration should be rolled back. As we enter the third year of the pandemic, with shootings still at double the 2019 level, we are at a stalemate: one side pushing for further reshaping of the justice system without minimizing the troubling jump in shootings and the other reverting to an old- fashioned reliance on the police without learning from what the past has taught us.

Just as in the 1990s, the NYPD engaged in a staggering act of courage by owning its role in controlling crime, another act of staggering courage is required now, that learns from the successes and mistakes of the past: this one shifting the center of gravity away from a model of public safety that defaults to police and coercion and towards a model that tips towards strengthening social ties through civic services. This new model should look at every possible idea that can defeat violence, whether it comes from the president, the police, the parks department or the people. It should mobilize all of the relevant resources of government, the nonprofit sector and the business community. And it should look to return policing to its proper and honored role as one of many civic services, with the entire enterprise of ensuring safety firmly under civilian leadership.

More specifically, here's how we should proceed:

1. Set a clear goal and organize with urgency, guided by data and radical transparency.

While, of course, our ultimate goal should be zero shootings, in the short term, our goal should be to reduce shootings by half, returning to the low of 2019. Setting a goal and having a plan unites all players—not just police—in a common enterprise. A commitment to collecting and looking at data regularly together will support a necessary radical transparency, with results displayed in real time to decision-makers and the public—showing what's working and what's not. It is what a functioning democracy demands.

2. Match the plan to the problem.

The plan must rest on a granular understanding of the people, places and dynamics driving the violence. Some features are long-standing: violence is highly concentrated in a few neighborhoods in the city; it feeds off of a supply of guns that we have little control over; it accelerates into cycles of retaliation, if not braked; and it is limited to a small number of people.

During the pandemic, there were more shooters, and they were shooting more often. The geographic boundaries expanded. The escalating nature of violence bore witness to the limits of enforcement in achieving long-term behavioral change. And while about half of the shootings were "gang-related" or related to an unspecified argument, half were not.

3. Identify every lever that can be used to reduce violence, focusing on those that produce the most safety with the least social and fiscal cost.

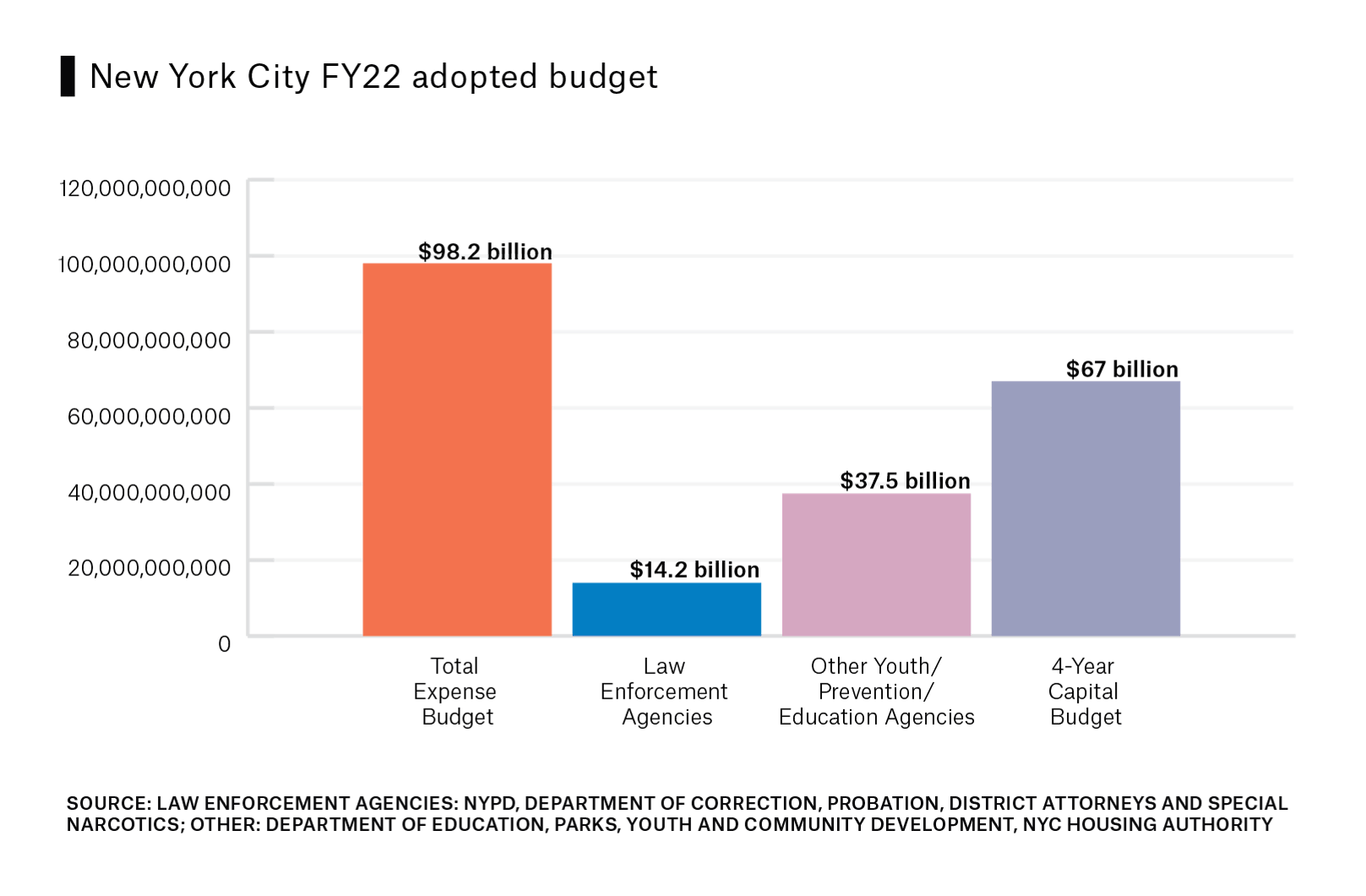

The city of New York spends approximately $90 billion every year to ensure the safety and well-being of its residents. The public debate tends to focus on the $14 billion the city spends annually on police, jails, prosecutors, defenders and probation when we discuss safety. To be sure, $14 billion isn't chump change, and we should scrutinize how much safety we get for every dollar spent here. For example, over the past eight years, city funding for these criminal justice services increased in real dollars by 17 percent while virtually every measure of activity—for example, arrests, arraignments, people in jail—for these agencies fell by half.

But the $37 billion spent on education, public housing, parks and youth programs, as well as the $67 billion spent on capital projects that shape the physical face of our neighborhoods, must be part of this solution as well. The authors in this edition of Vital City have outlined some examples. But the investments cannot just be a pile of programs, they must be part of a coordinated strategy. The components need to be chosen with care, supported appropriately and monitored with rigor. Here is one broadbrush way it could fit together:

- Focus on the physical city, encouraging the active and positive use of physical space. For example, the same locations have been the site of violence for generations. Physical changes—inviting more positive activities, opening up sight lines, better lighting have reduced nighttime felony crime in New York City by over 30 percent and reduced gun violence by 29 percent in Philadelphia.

- Focus on economic stability, including employment for young people as part of a continuous ladder of opportunities. In New York City, summer youth employment was found to decrease both incarceration and mortality among participants, and a study in Chicago also found reductions in violent crime arrests among participants. Additionally, those receiving emergency financial assistance in Chicago were arrested 51 percent less often than individuals who did not receive funds.

- Deploy police for what they do best, solving crimes and focusing on the small number of people who are driving the shootings and the small number of places with recurring violence. According to the NYPD, 700 individuals are linked to 1,700 incidents involving illegal firearms. A study in New York City found that after gang takedowns, shootings fell by nearly one third in the following year.

- Use analytics fiercely to understand what is driving crime—including social stressors—and be ambidextrous in deciding whether the use of force or participation is more effective in stopping it.

- Use analytics and feedback from New Yorkers in real-time to see what effect—for good and for bad—all of the above is having.

4. Create a new civic infrastructure that is as robust and as well-developed as the formal criminal justice system.

Cops have been put on the front lines of every social problem that manifests itself on the street. There is a broadening recognition that this is not wise, effective or fair, either to the police or to New Yorkers. But the effort to build another structure has been piecemeal and partial. Building on what's already in place, we can develop a civic infrastructure for safety that is as robust and deployable as the police. This would include:

- Expanding the NeighborhoodStats. These currently exist in the handful of neighborhoods with the greatest challenges, from crime to asthma. We should ensure that these efforts, which now feed to a citywide NeighborhoodStat, are directly connected to the deputy mayor for public safety so that problems and solutions can be seen citywide.

- Integrating into the NeighborhoodStats the network of community-based services that are directly identifying people and places in need, as the Brownsville Safety Alliance is doing now, and as other cities have so successfully done. The Crisis Management System should be incorporated into this effort so that violence interrupters can be seamlessly connected to city resources, and their innovations can be quickly replicated when effective and course corrected when they aren't. This will relieve the current pressure on violence interrupters to be the solution to every problem—which they cannot and should not be.

- Piloting a new approach to justice in a single precinct. Using one precinct as a pilot, we should gather police, other government agencies and residents to think through what functions police should do and what functions are more effectively performed by paid resident groups, by other city agencies or through other methods than programs and patrol what functions are not needed at all. To start, the group might consider how the budget of a precinct might be used to greatest effect if it were devoted to using every tool on the table, not just those offered by law enforcement.

Over the past half century, we have experienced several pendulum swings in how we address crime. In the 1970s and 1980s, when crime was rising rapidly, the mantra that "nothing works" seemed to express the despair of the moment. In the 1990s, a new era of heavy reliance of police and the criminal justice system appeared to bring crime under control. For the past decade or so, we have been reckoning with the harms that this heavy reliance brought. Going forward, we need a different model that encompasses a far broader portfolio of solutions and taps into the most important and durable source of safety: the people themselves.

How would our world look different if we adopted this integrated social fabric approach to safety? Next year, when shootings are at half what they are today, the president would visit New York City accompanied not only by the attorney general but by the secretaries of Housing and Urban Development, Health and Human Services and Labor. They would meet with the mayor and his deputy mayors at city hall in the well-named Committee of the Whole room. Looking at a map of the city, girded by an understanding of what had worked and what had not, they would set down their markers to reach the ultimate goal, step by step, of shootings at zero. ◘