How drivers, pedestrians and bicyclists can all get clearer views

Across the country, cities are rethinking how they use streets. In New York City, one of the most fiercely contested issues is the design of intersections, largely focused on whether to keep corners clear of parked vehicles in order to make it easier for pedestrians and drivers alike to see around the corner, a change that's referred to as "daylighting."

Safe-street advocates are rallying for universal daylighting at all intersections; a bill currently before the City Council would do just that. On the other hand, the city's Department of Transportation released an analysis earlier this year, while criticized by councilmembers and safe-street advocates for faulty use of data, claiming that daylighting does not necessarily make intersections safer. Many drivers and their representatives also argue that the estimated (though disputed) cost of over $3 billion could be better used elsewhere.

The current debate focuses on providing clear curb space on both sides of all four corners of an intersection, with advocates saying this is required for better sight lines. DOT and others opposing a change claim that daylighting would take up too much curb space currently used for parking, and that daylighting in fact encourages speeding, making streets more dangerous.

Both sides are missing the real issue: there are different safety considerations at different areas of an intersection, and we need different design strategies to address each.

Specifically, conditions are very different when drivers are entering an intersection than when they are exiting it. When drivers are entering, we want to optimize visibility. When drivers are exiting, improving cones of vision is no longer the issue; we just want to ensure that drivers stay far away from the curb, and slow down. Who amongst us has not almost had our toes run over by a driver making a right turn too close to the curb? This difference between vehicles entering and exiting has not been addressed in the discussion to date, or even by other design standards.

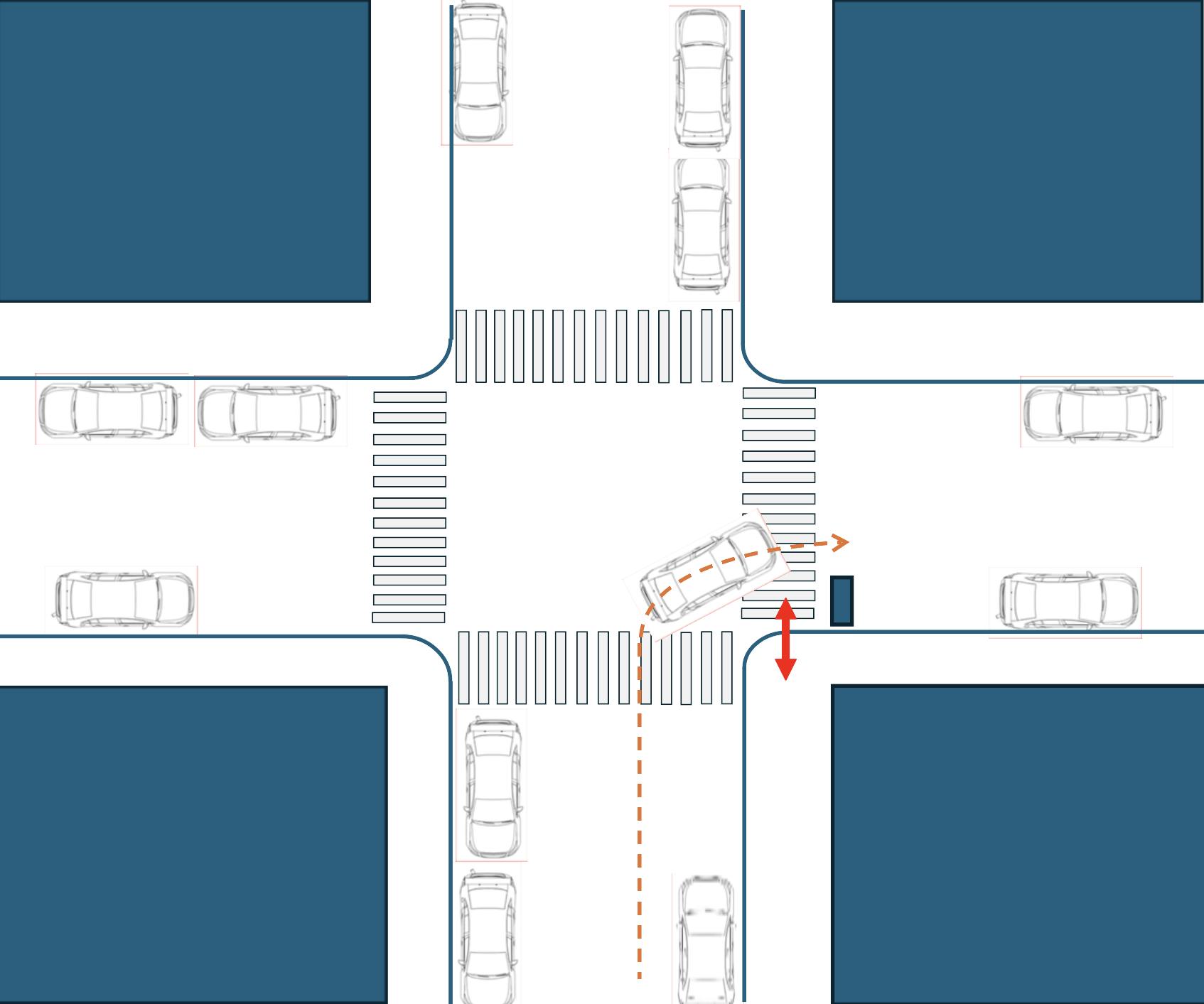

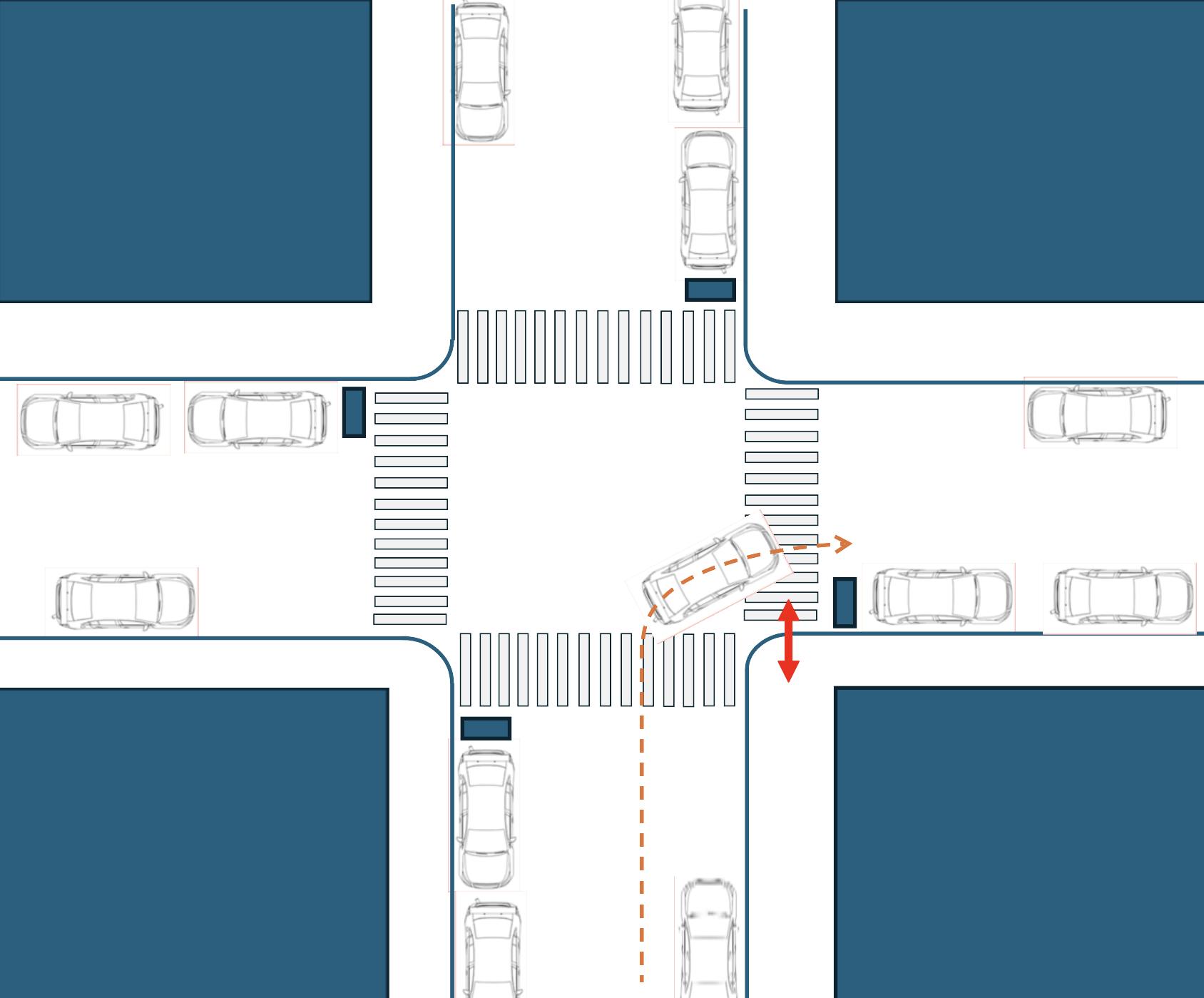

What is needed now is an informed design standard that prioritizes clear lines of sight when drivers are approaching an intersection, and provides a barrier in the curb lane for when they exit. Call it Daylight Savings. Developing this standard will save lives by improving upon the aspects of universal daylighting that actually contribute to public safety, and, as a bonus, it has significantly less impact on existing curb uses.

A dispassionate geometric analysis of how intersections work would lead us to such a standard, which isn't political or ideological — just practical.

A deeper dive into what's really going on at intersections

At a typical intersection, there are two primary causes of crashes: restricted visibility, and vehicle speed. We can design for both, but the optimum design solution is different at each side of a corner. Here's why.

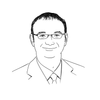

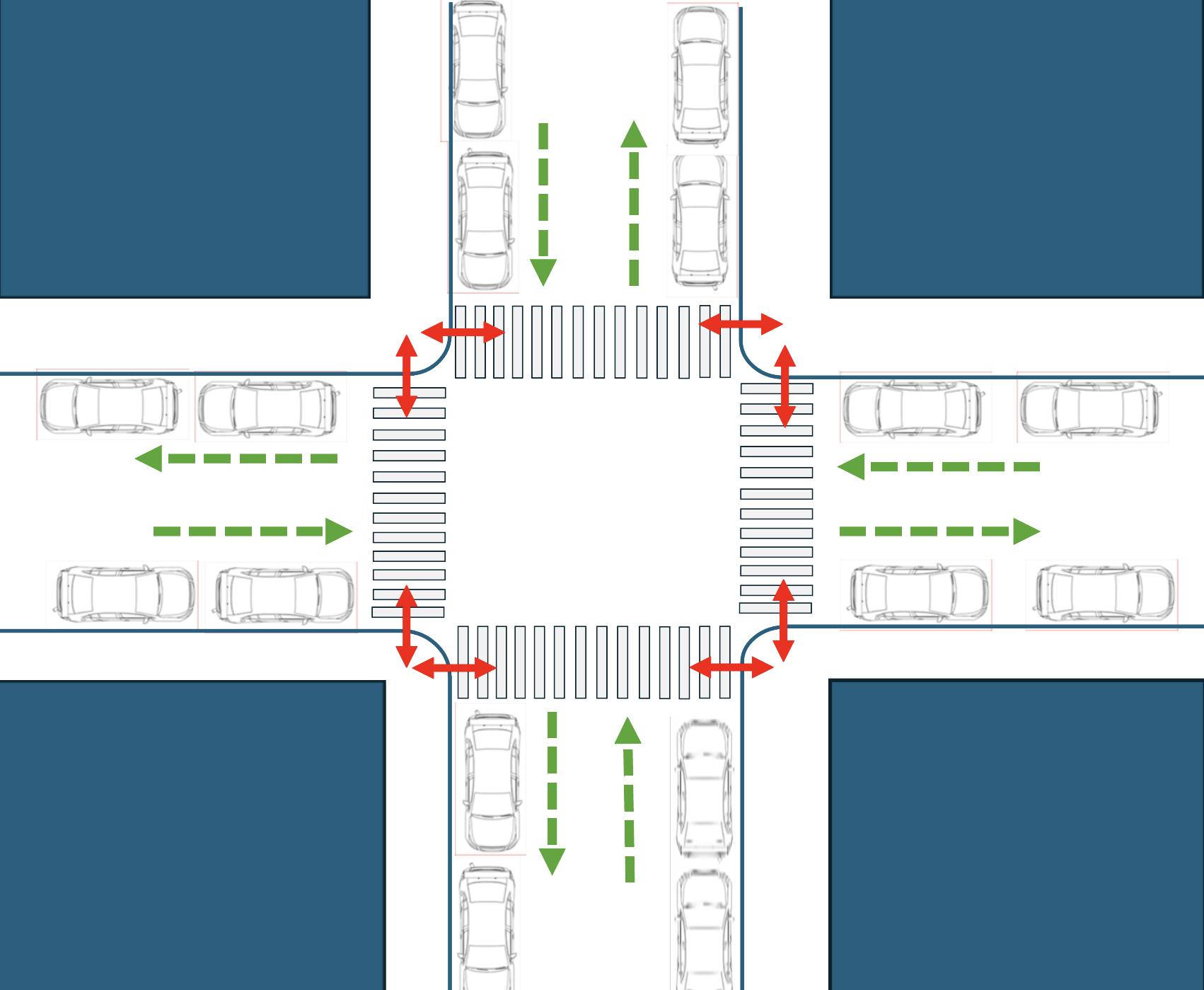

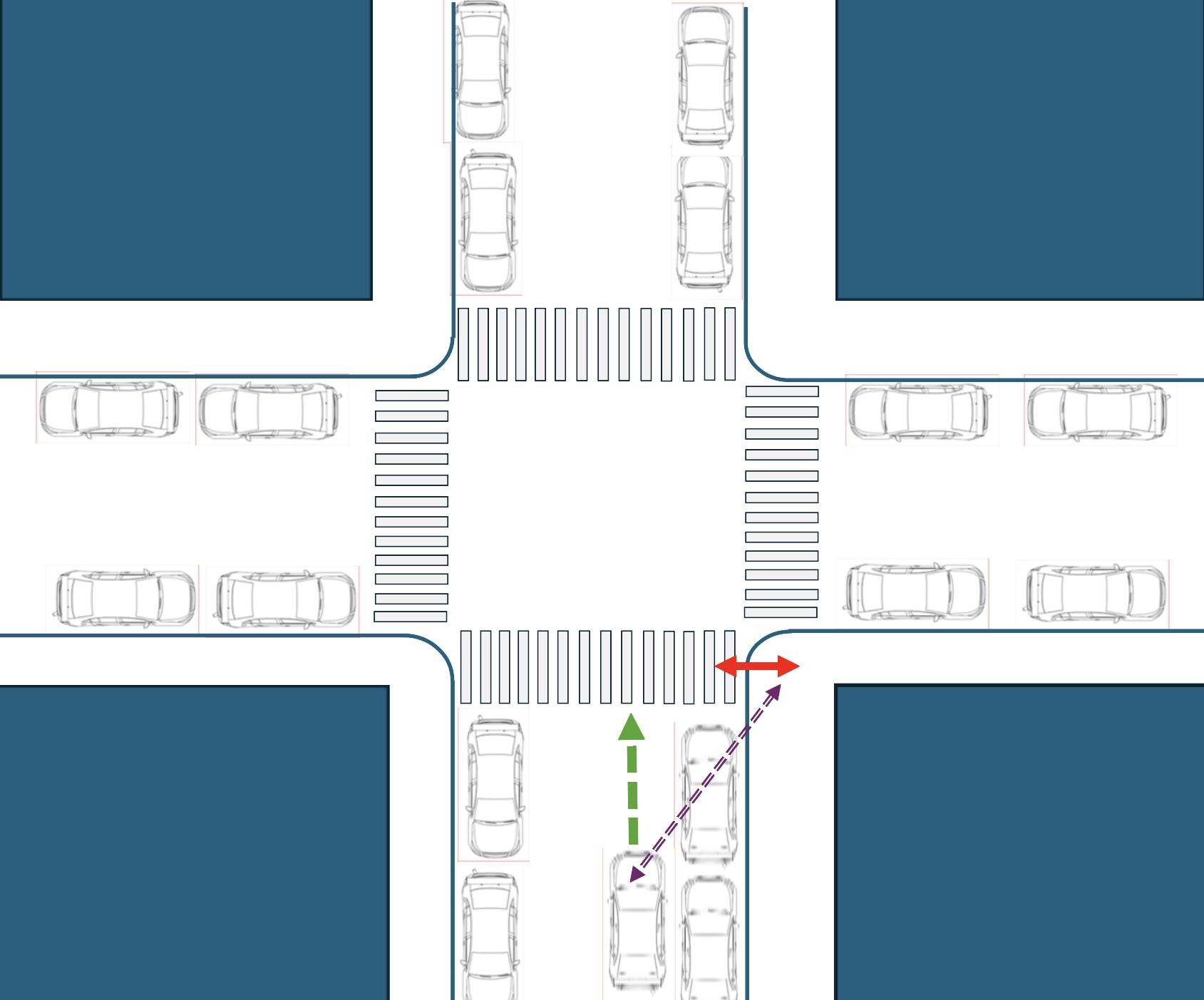

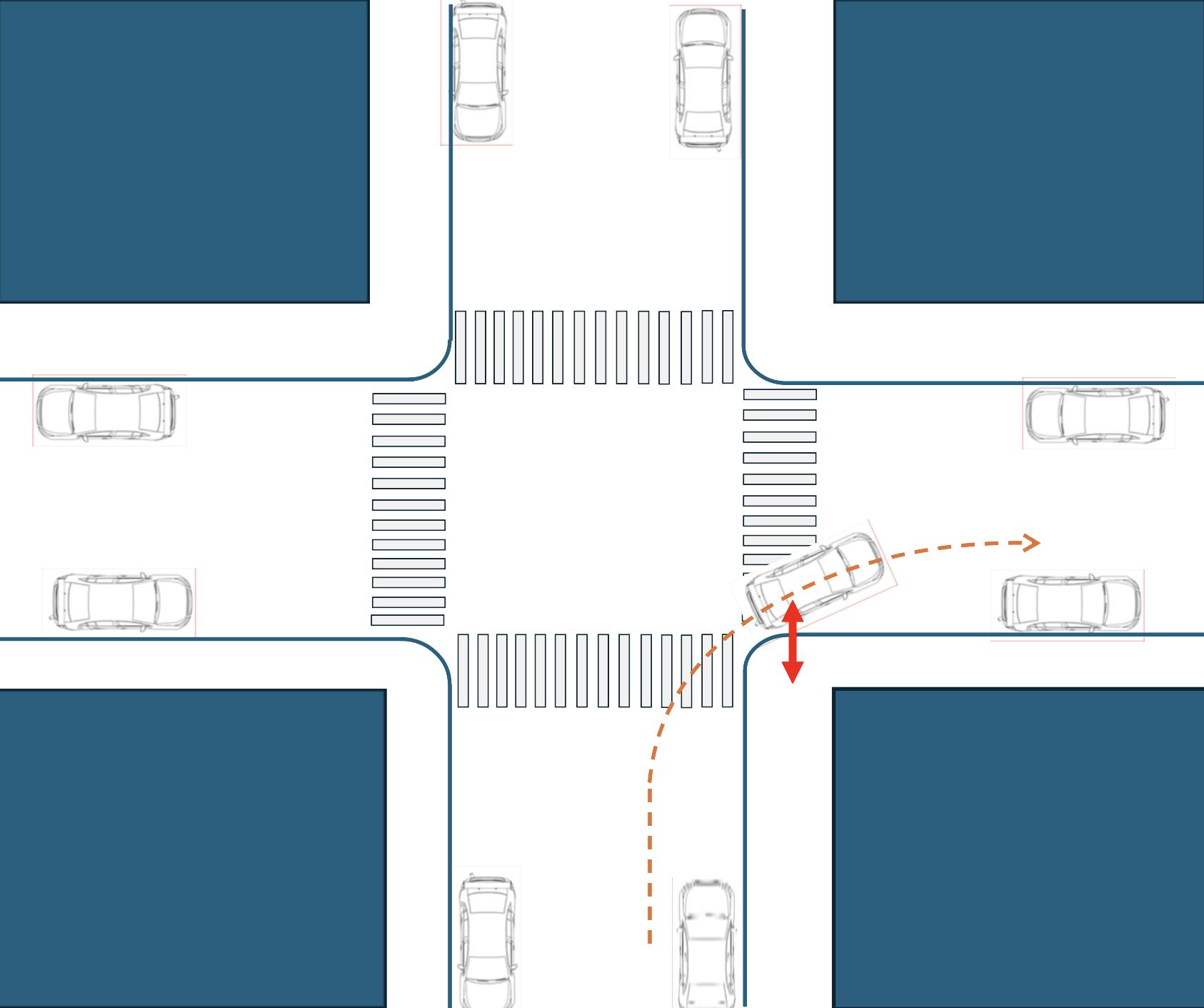

Each corner has two paths of travel for pedestrians, one crossing each street. With four corners, that makes eight paths of travel. Four of them involve drivers entering the intersection, and four involve drivers exiting it. In the diagram below of one corner, the top side has drivers entering the intersection, and the right side has drivers leaving the intersection. There are, of course, variations depending on one-way streets, bike paths and other issues. But let's keep it simple, and typical, for now.

When drivers approach the intersection, vehicles parked close to the crosswalk can block sight lines for both drivers and pedestrians. Here's what it looks like in real life. The white truck on the left blocks sight lines for both pedestrians and drivers entering the intersection, creating an unsafe condition.

Clearly, if there were no vehicle parked there, there would be a safety benefit due to the wider cones of vision for both the driver and the pedestrian.

However, for a driver exiting the intersection, the situation is different. Visibility for pedestrians of a moving vehicle exiting the intersection is already barrier-free. Removing parked vehicles at that (top) location doesn't improve sightlines or safety — instead, it allows drivers to make a wider, faster turn.

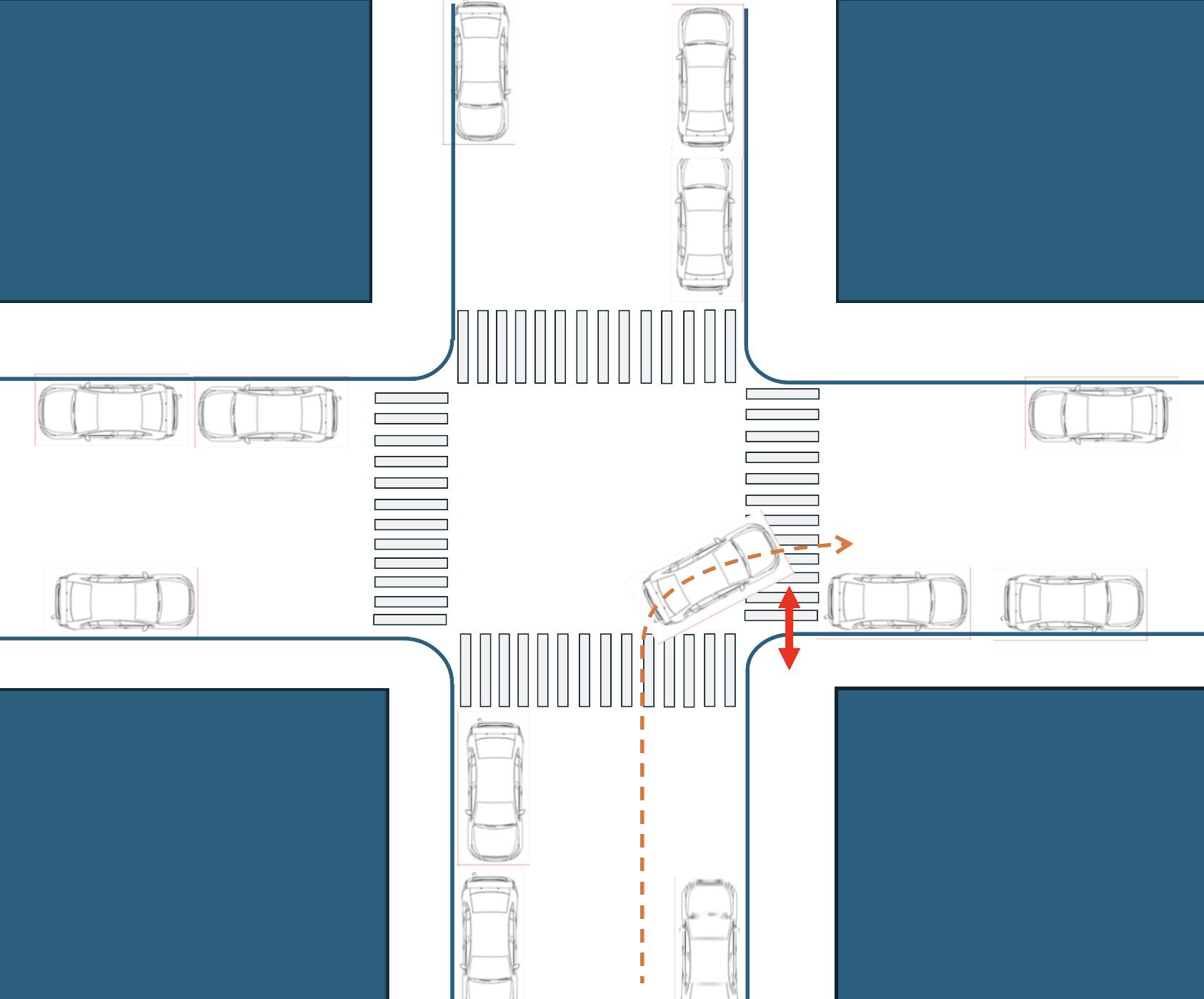

This is the condition that the DOT correctly identifies as encouraging higher speeds. Not because of more or less visibility, but because of the well-understood and documented fact that cars travel faster on wider turning radii than on narrower ones.

Conversely, a car or other obstacle in the curb lane here requires a driver to make a tighter turn, which naturally slows them down. Here's what this looks like in real life.

The white truck on the left does not impede views of vehicles exiting the intersection, and in fact slows traffic turning right onto this street, providing a safer condition.

Unfortunately, the DOT's January 1 Analysis Of Daylighting And Street Safety fails to recognize the key differences between approach and exit sides of intersections, and thereby misses key differences. Instead, they suggest, counterintuitively, that increased visibility in general can in fact encourage faster vehicle speeds and actually contribute to driver/pedestrian crashes. In a recent editorial, the City's transportation commissioner and safe-streets advocate Ydanis Rodriguez argues that only "hardened" daylighting — meaning replacing a parked car with a physical barrier — can have safety benefits, while calling for more rigorous analysis. If the January 1 report is an indication, that rigor, beginning with a recognition that the issues are different at different areas, remains to be put into place.

A better way

Understanding the key differences in conditions at even the simplest of intersections suggests that a finer approach to the design of intersections is warranted. It's pretty simple, really: Intersection design should ensure better cones of vision on the approach side of an intersection and discourage high speeds at the exiting side.

Of the eight start points for pedestrians, only the four "driver-entry" points would benefit from better sight lines. In contrast to the idea that full daylighting is always safer, the other four paths of travel would actually benefit from an object located near the crosswalk, be it a parked car, raised planter, bike rack or other public amenity. Since we can't guarantee that a car will always be parked there, it makes sense to place some sort of barrier that requires moving vehicles to make a tighter, and therefore slower, turn.

Some advocates for universal daylighting have made the case that taking parking space away is, in and of itself, a good thing, and that daylighting also provides the opportunity to create rain gardens. These are separate concerns from the safety issue, which is my focus here.

A "Daylight Savings" approach, with no parking on the approach side but with a barrier at the curb lane on the exit side, whether it's 2 feet wide or 20, would result in a reduction of the effective turning radius for vehicles making right turns, thereby calming turning speeds at the moment pedestrians are most vulnerable, while still improving all relevant sight lines. This does not preclude parking at 50% of the locations.

In short, if what we care about most is pedestrian safety, the debate shouldn't be over whether to allow or disallow automobiles at all eight locations of an intersection. There's good reason to bar cars from parking in four of those spots — while keeping them and even placing other smallish, turn-slowing objects in the other four.

A Daylight Savings approach improves upon the true safety benefits of daylighting, while reducing construction and saving curb space. It's a lighter, quicker, cheaper — and maybe more politically palatable — way to achieve safer streets.

════════════════════════════════════════

New York is entering an historic and pivotal transition. Mayor-elect Mamdani faces big problems on housing, safety, mental health, transit and more.

Vital City is uniquely positioned to offer clear, practical guidance rooted in evidence. Ideas that could actually be implemented and work.

But to meet this moment, we need to grow.

That's why, this year, for the first time, we're asking our readers to support Vital City directly. We're aiming for 700 inaugural supporters by December 31.

Your support will help us expand our editorial capacity, strengthen our operational support and continue delivering thoughtful, relevant and informative work in 2026.

If this article informed your thinking, challenged you or helped you understand the city more clearly, please consider supporting the work behind it.

Make your tax-deductible gift and help us reach 700 supporters.