The recent rise in violence has been concentrated in areas characterized by poverty and racial segregation.

At the start of the 1960s, just over four out of every 100,000 Americans were murdered each year. The murder rate rose sharply during that decade and then fluctuated between eight and 10 murders for most of the 1980s and early 1990s, before it began to fall in the mid-1990s. By 2014, the murder rate had fallen to 4.4 murders for every 100,000 people, back to where it stood at the beginning of the 1960s. That year, 2014, was one of the safest in our nation's history. It is also the year when the trend shifted. In the years since 2014, the murder rate has risen by almost 50 percent, to 6.5 murders for every 100,000 people.

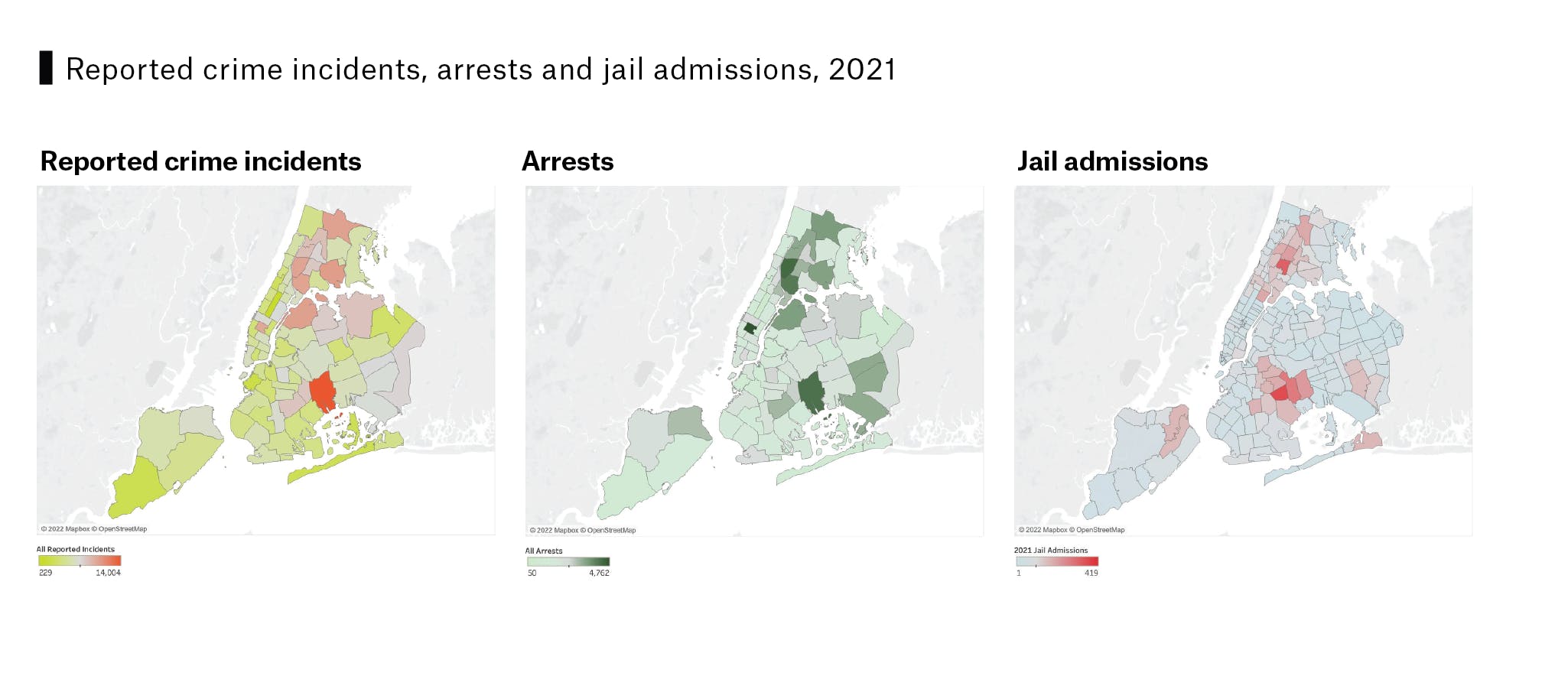

This is the latest headline that has been broadcast out to the nation. But the headline misses a fact about American violence that is crucial to understanding both its causes and its consequences. In many cities with relatively high levels of violence, some communities are untouched by shootings and assaults, while others experience extreme incidents of violence on a regular basis. One of the most robust findings about violence is its concentration within a small number of street segments, intersections, city blocks and neighborhoods, characterized by racial and economic segregation. The spatial distribution of violence is remarkably stable: in a study of violence in Chicago's neighborhoods over 56 years, we found that the most violent Chicago neighborhoods in 1965 have continued to have the highest levels of violence in every period since, all the way through 2020.

Shifting our perspective from cities to neighborhoods changes the meaning of the latest national trends. From 1991 to 2014, when the murder rate fell by roughly half, the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, and the most disadvantaged segments of the population, benefited the most. Life expectancy rose most sharply for Black men, the racial achievement gap narrowed the most in states where violence fell the furthest and economic mobility improved for young people who were raised in places where violence was steadily falling.

When violence rose in the United States from the 1960s to the 1990s, it was felt most acutely in areas marked by concentrated poverty and racial segregation.

But as violence has risen over the last six years, the same communities have been hit hardest. When we analyzed data on fatal shootings from the 100 largest U.S. cities, we found that the recent rise of violence has been concentrated in areas characterized by poverty and racial segregation. Over this period, neighborhoods with lower poverty rates experienced a 59 percent increase in fatal shootings. High-poverty neighborhoods experienced an 89 percent increase. In neighborhoods composed of a majority of Black Americans, the rate of fatal shootings rose by 87 percent, while all other neighborhoods saw a 60 percent increase.

These trends are a continuation of a long-term pattern. When violence rose in the United States from the 1960s to the 1990s, it was felt most acutely in areas marked by concentrated poverty and racial segregation. When violence fell from the 1990s to the 2010s, it fell the most in these same communities. Violence continues to be concentrated in neighborhoods that experience multiple forms of disadvantage, from poverty to disease to segregation to joblessness. The question is why?

The answer takes us back to the middle of the 20th century, when a set of social and economic forces combined with federal, state and local policy to create a crisis in American cities. As jobs in the manufacturing sector began to disappear, middle-class families took advantage of subsidies to leave central cities, joblessness rose and poverty became more concentrated in central city neighborhoods left behind. As political power and government resources shifted to the suburbs, public housing complexes and schools deteriorated, sidewalks were not maintained and public parks were left untended.

Instead of responding to this set of challenges with investments in central city communities, the federal government disengaged from urban issues and responded with punitive social policies that have exacerbated the problems faced by urban populations. The abandonment of central cities began under President Nixon, who argued that urban neighborhoods should be left on their own to deal with rising poverty and joblessness.

Our nation's response to extreme urban inequality created the conditions for violence to rise.

In the subsequent decades, federal investments in central cities have typically been implemented on a small scale and only for a limited timeframe. Never has there been a systematic effort to deal with the problem of urban poverty through sustained, large-scale investments in the people and the institutions of the nation's city neighborhoods. Punishment, on the other hand, has been the most consistent response to urban crime, violence and poverty. Harsh state policies, such as eliminating parole and establishing mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses and violent crimes, combined with more aggressive policing and prosecution at the local level to push more Americans into the apparatus of the criminal legal system and to keep them enmeshed within this system for longer durations of time.

Our nation's response to extreme urban inequality created the conditions for violence to rise. As political influence and public funding decline, core community institutions like schools, daycare centers, parks, playgrounds, libraries and other features of the built environment are less likely to be supported and maintained. Flagging investment in local infrastructure leads to poorly lit spaces, abandoned lots and empty buildings that are vulnerable to becoming areas of violence. Robert Sampson's research on collective efficacy demonstrates how the concentration of social and economic disadvantage can undermine social cohesion and trust among residents, making it less likely that they will take active steps to reinforce shared expectations for behavior, work together to solve problems and achieve commonly shared goals for the community.

The relationship between disadvantage and violence is reciprocal. Inequality causes violence, but violence amplifies inequality. Violence disrupts learning, leads people to retreat from public spaces, leads businesses to close shop and leads parents to seek a way out of the neighborhood. In the U.S. context, the prevalence of violence frequently leads to a shift in the central institutions and actors within a neighborhood. Representatives of the criminal legal system, including police officers, parole officers, school safety officers and detectives become dominant figures in public spaces, and squad cars, sirens and police tape become common features of the landscape. When we mapped data on shootings with data on police violence and incarceration, we found that the neighborhoods where violence is concentrated are the same neighborhoods that have experienced extreme levels of imprisonment and police shootings.

It is crucial to avoid the tendency to report these statistics on poverty, race, incarceration and violence without an accompanying explanation of the link. In the United States, long-term disinvestment in central city neighborhoods has reinforced segregation by race, ethnicity and income, weakening community institutions and undermining community residents' capacity to work together to solve common challenges. Our nation's response to violence, and to the challenge of extreme urban inequality, has relied heavily on the institutions of punishment. This has compounded disadvantage. Communities with high levels of violence are also places where police violence is more common and where a large segment of the population is entangled within the expansive apparatus of the criminal legal system. It is a mistake to look at this and conclude simply that where there is violence; we should expect high levels of incarceration. The pattern of compounded disadvantage is a result of the unique American response to the challenges that emerged in central cities in the late 1960s: a response which featured the dual strategy of abandonment and punishment.

The fall of violence from the early 1990s to the mid-2010s makes clear that high levels of violence are not inevitable. One of us (Sharkey) has argued that violence fell because of a set of efforts to transform urban space, through both aggressive policing and intensive surveillance as well as through the mobilization of local community organizations who worked to reclaim public spaces and build stronger neighborhoods. But the fall of violence was precarious, because the dominant methods to respond to violence haven't changed over time. The United States has not undertaken a large-scale, sustained agenda of investment to confront extreme urban inequality.

Our national approach has meant that when violence falls, the most disadvantaged communities will benefit the most, and when violence rises, it is these same neighborhoods that suffer the most severe consequences. And through the ebbs and flows, our reliance on the police and the prison means that a large segment of the population will experience the dislocation that comes with a period of imprisonment, and entire communities will continue to feel the resentment that comes from seeing their neighbors and family members mistreated by the police. The trends that we have documented, and the spatial convergence of violence, segregation, poverty, institutional decline and incarceration, lead us to the following conclusion: it may not be possible to address the challenge of American violence in a sustainable way without addressing the much larger challenge of extreme urban inequality. ◘

Further Reading

John Clegg and Adaner Usmani, "The Economic Origins of Mass Incarceration," 3 Catalyst 3, 9-53 (2019).

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, (Harvard University Press, 2016).

Robert J. Sampson, Great American City, (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Robert J. Sampson & William Julius Wilson, Toward a Theory of Race, Crime, and Urban Inequality 312-325 (Routledge, 2020).

Patrick Sharkey, Uneasy Peace: The Great Crime Decline, the Renewal of City Life, and the Next War on Violence, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018).

Patrick Sharkey, "The Long Reach of Violence: A Broader Perspective on Data, Theory, and Evidence on the Prevalence and Consequences of Exposure to Violence," Annual Review of Criminology 1:14.1-14.17 (2018).