Debates about disorder and crime are heating up, with major implications for urban policy.

Nearly three years into a pandemic that knocked the world on its heels, most people are back outside — and some don't like what they see.

In New York City, there's been an outpouring of concern about disorder in public spaces, from minor violations of social norms to serious crimes. Few dispute that official measures of crime are up relative to historic lows achieved pre-pandemic, but what the data means and how to respond are hotly contested. And running beneath the debates are consequential questions about how to address society's biggest social challenges. How the fault lines undergirding their arguments shift or crumble could affect urban policy for years to come.

Welcome to Fear City?

"Disorder" is a notoriously vague concept, generally defined as violations of physical order and social norms that don't rise to the level of crime, but which George Kelling and James Q. Wilson famously theorized could lead to more serious offenses if left unaddressed. The idea of a slippery slope between disorder and crime — though short on empirical verification — has allowed for a fairly unfocused conversation about the state of New York City, where complaints about any aspect of public space blur into debates about personal safety.

And the complaints have been loud and unrelenting: about people sleeping on the subway, turnstile jumping, trash on sidewalks and streets, "smoking, open drug use, and vandalism" in the transit system, and rare but lurid violent crimes that tabloids prominently cover in their pages. In May, Mayor Eric Adams declared (and later walked back), "In my professional career, I have never witnessed crime at this level."

Official data suggest a cooler response may be merited. As of October 2022, murders were down 14 percent compared to the year prior, according to the Police Department, whereas other major felony offenses were up, particularly grand larcenies. Robberies and burglaries remained below levels the city tolerated as recently as 2013. That historical context is rarely part of the popular narrative, which is basically that New York City is coming apart at the seams.

A diagnosis to fit the desired treatment

Those drawing attention to disorder invariably define the problem in terms that favor their preferred solution. Broadly speaking, where progressives say disorder reflects a weak social safety net, conservatives blame it on the loosening of checks against antisocial behavior, both in society's norms and the state's powers to enforce them.

This may seem like an academic debate or political noise to many New Yorkers residing in neighborhoods where crime and punishment are lowest — but some leading voices are harnessing the narrative of rising disorder to proposals with enormous stakes for the future of the city.

Some attribute what they see as deteriorating conditions to landmark bail reforms the legislature made in 2019, which substantially reduced jail detention by mid-2020. In early 2022, under an onslaught of criticism, the legislature partly rolled back the reforms, but critics (including Mayor Eric Adams) won't let up. Former Queens Executive District Attorney Jim Quinn recently argued that "bail reform has been a failure." (The reforms were crucial to a plan to reduce the city's jail population to 3,300, who could then be housed in borough-based jails meant to replace violence-ridden Rikers Island. Now the daily jail census is hovering around 5,800. Quinn did not address how the city would meet its statutory obligation to empty the island by 2027.)

Similarly, former police commissioner Bill Bratton has beaten the drum for refocusing police on low-level, quality-of-life offenses that he maintains have "grown into violent crimes."

The series of robberies being seen across New York City is a result of not fixing the Broken Windows — failure to address menacing motorbike riders with meaningful prosecutions and consequences. The disorder has now grown into violent crimes. pic.twitter.com/452kZiCVAa— Bill Bratton (@CommissBratton) August 30, 2022

Bratton also applauded a recent uptick in arrests of misdemeanor crimes, particularly fare evasion and petty theft. Mayor Eric Adams has responded forcefully to other types of disorder, too, including by clearing homeless people from the subways and from encampments in hundreds of sweeps, and defending the arrest and strip search of an unlicensed mango seller. "Next day is propane tanks being on the subway system. Next day is barbecuing on the subway system," he explained.

Progressives have pushed back on the premise that disorder and crime are up. Alec Karakatsanis, executive director of the nonprofit Civil Rights Corps, argued, "An emergency focusing on interpersonal 'crime' committed by poor people is being manufactured before our eyes." City Council Member Tiffany Cabán tweeted that violent crime on the subway remains a one-in-a-million event and "fear-mongering politicians and corporate media outlets" are trying to scare New Yorkers. Even NYPD Chief of Department Kenneth Corey said the notion that the subways are dangerous is overblown, and drew attention to data showing crime there is down from pre-pandemic levels. "There is a narrative that's inaccurate that's driving people's perceptions of how safe the subway really is," he said. Enjoying a soothing trumpet solo at the 14th Street subway station, television host Errol Louis gently suggested New Yorkers believe their own eyes and ears over the hype, which kicked up its own firestorm.

Going home on the violent NYC subways. Riders paralyzed with fright. pic.twitter.com/icOvJ4MDV9— Errol Louis (@errollouis) October 11, 2022

Progressives say homelessness, addiction and crimes of poverty call for strengthening public services rather than deterrence through starker penalties. Jacquelyn Simone, policy director at the NYC-based Coalition for the Homeless, told NPR: "Policing and criminalization are not the responses to what is fundamentally a housing and mental health crisis." Cabán, who criticized homeless sweeps as violent and cruel, proposed A New Vision of Public Safety for New York City that would build out community-based services and replace police in schools and traffic enforcement with unarmed counselors and responders, among other changes. But is the public receptive to her urging that they find "better ways of solving problems than simply summoning police"?

Subway violence is a one-in-a-million event.

As a believer in a violence-free NYC, I still think that's one too many, but let's not let fear-mongering politicians and corporate media outlets scare us into thinking we have a dangerous, scary public transit system. pic.twitter.com/NEzvDLCH19— Council Member Tiffany Cabán (D22) (@CabanD22) September 26, 2022

West of the Hudson

The protagonists and props are different, but similar storylines are playing out in other major American cities, with progressive prosecutors fighting to hang on in Philadelphia and Los Angeles, and in San Francisco, where perceptions of increasing disorder helped oust recently elected District Attorney Chesa Boudin.

In a 7,700-word essay published in The Atlantic the day after Boudin's recall, writer Nellie Bowles made the seductive argument that San Francisco has been a test-case for a failed laissez-faire approach to disorder, and the recall signified its repudiation. She rolled together the city's longtime tolerance for open-air drug use and homelessness with a recent rash of car break-ins and organized retail crime — and pinned the blame on Boudin's reforms, which she said "allowed criminals to go free to reoffend." His supporters, she wrote, were "idealists" who were "ignoring" results and had "lost the plot." But in an interview with Mayor London Breed, who promised more policing and less tolerance for "all the bullshit that has destroyed our city," Bowles did not press for an explanation of how this would right the city's public spaces, even as she conceded the strategy was "mostly symbolic."

If they want to keep their jobs, civic leaders may have no choice but to figure out how to deal with disorder. In a June article, Slate writer Henry Grabar reasoned that even if homelessness is not meaningfully correlated with crime, city leaders have to address it assertively and effectively as if it were. Democrats in big cities are proving particularly inept at doing so, he says, because evidence-based solutions — like overcoming NIMBYism to build shelters and affordable housing — divide their reliable voters. At least as Grabar sees it in California, "Democrats' inability to address the homelessness crisis is going to cost them generational progress on criminal justice, as the forces for reforming the police go into retreat."

And nationally, in the run-up to midterm elections, Republicans are making crime a major part of their pitch, although Democrats are pushing back. This discourse is particularly disheartening since the FBI's woefully incomplete 2021 data leave open the possibility that crime nationwide "went up, went down or stayed the same."

The echo chamber

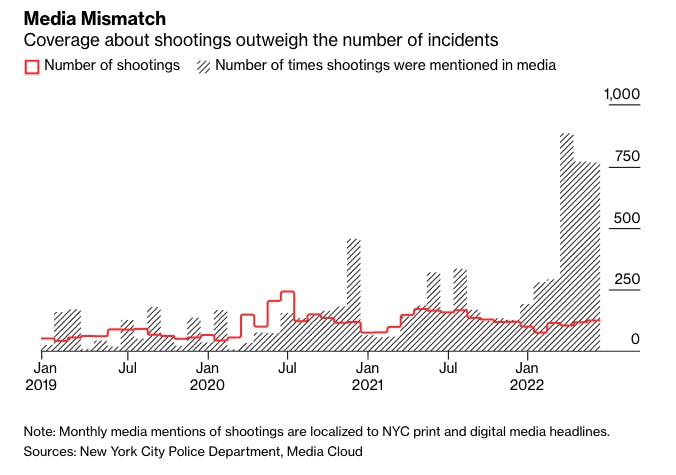

Just as police and prosecutors have discretion, so too do reporters and editors, and their coverage plays an intrinsic role in these processes by echoing and amplifying fear. Bloomberg reporters showed that coverage of New York City's uptick in violence far outstripped the actual changes in crime. So it's no surprise there's been a measurable increase in the share of the public uneasy about crime — fears that then become the grist for further coverage, a churn podcaster and writer Adam Johnson recently dubbed "Vibes Crime Reporting."

Once established, the narrative of a deteriorating society justifies news interest in stories that might not have passed muster before — like that of a homeless man in Prospect Park who purportedly hit a dog with a stick such that the dog later died. In detailed coverage of the incident's aftermath, the New York Times gave the dog's owner abundant space to vent: "This person is attacking people and killing dogs. He's targeting women and dogs. He's violent. He should not be in the park. He should be locked up and paying for his actions." The underlying message: be afraid.

John Oliver recently devoted an episode of his HBO show Last Week Tonight to daily crime reporting and the dangers of uncritically amplifying police communications, but old habits are hard to break. And a public keen to reestablish its sense of security is unlikely to take comfort from the explanation that its perceptions are divorced from the facts. As Johnson acknowledged, "The vibes may be unscientific, but they are real."

It's a precarious time, and where it leads will depend on what happens to perceptions of crime, and who gets the credit — or takes the blame.