Mayor Eric Adams has reassigned hundreds of officers to “Neighborhood Safety Teams” that he says will go after guns and the people who use them.

Today’s piece by Ted Alcorn—a journalist and the former research director at Everytown for Gun Safety—takes a look at New York Police Department’s newly deployed anti-gun teams. This is first in a series of articles that will examine pressing questions facing the city, and we invite feedback from our readers on topics that bear similarly close examination.

New York City has decades of history with street patrols specifically focused on illegal gun possession, and they’ve been dogged by controversy, including the shooting of an unarmed civilian, Amadou Diallo, in 1999 and the strategy of stop-and-frisk that was found unconstitutional as practiced in 2013. In the summer of 2020, then-Police Commissioner Dermot Shea disbanded the street crimes unit, acknowledging that the harms outweighed the benefits of this approach.

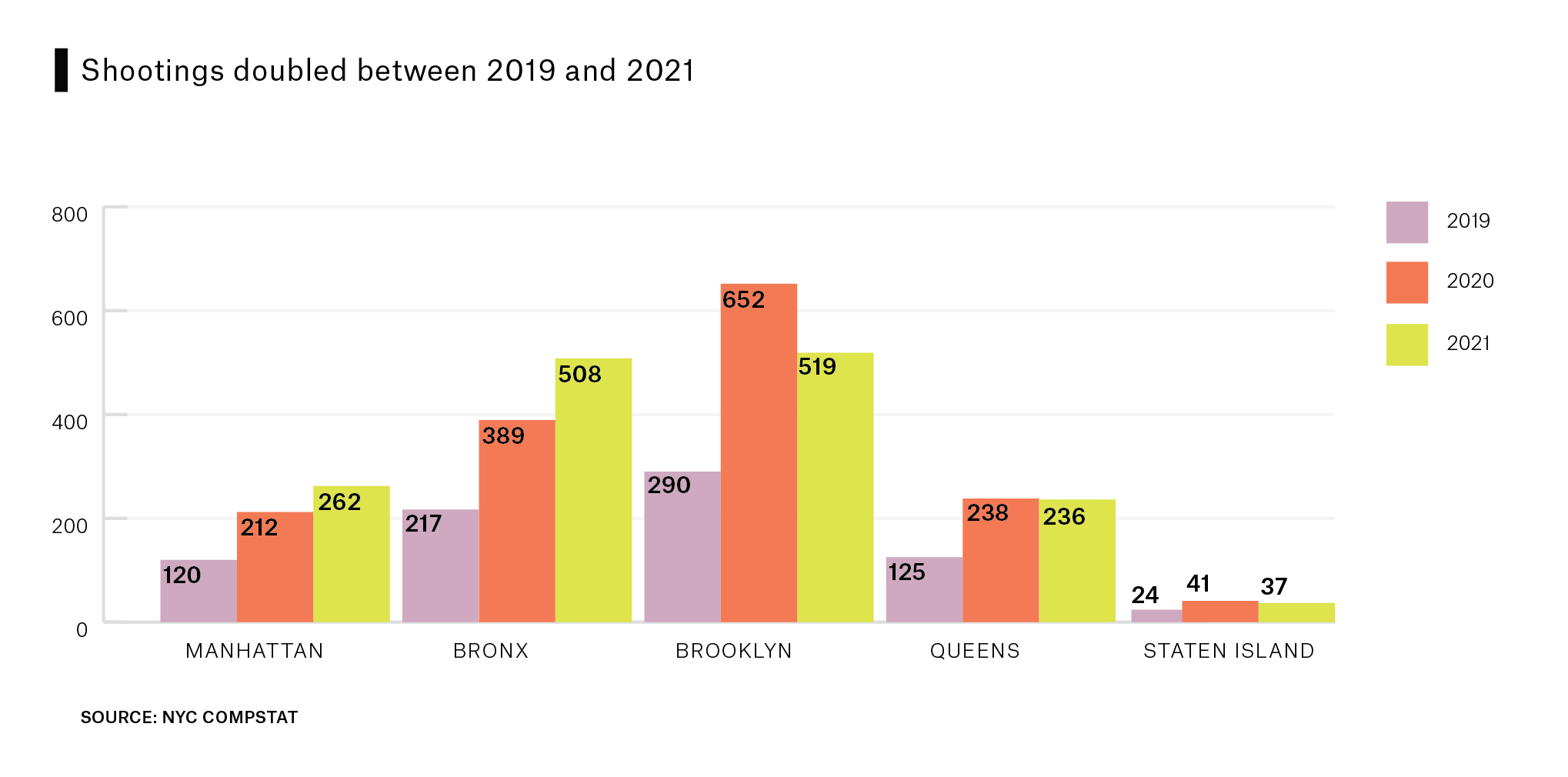

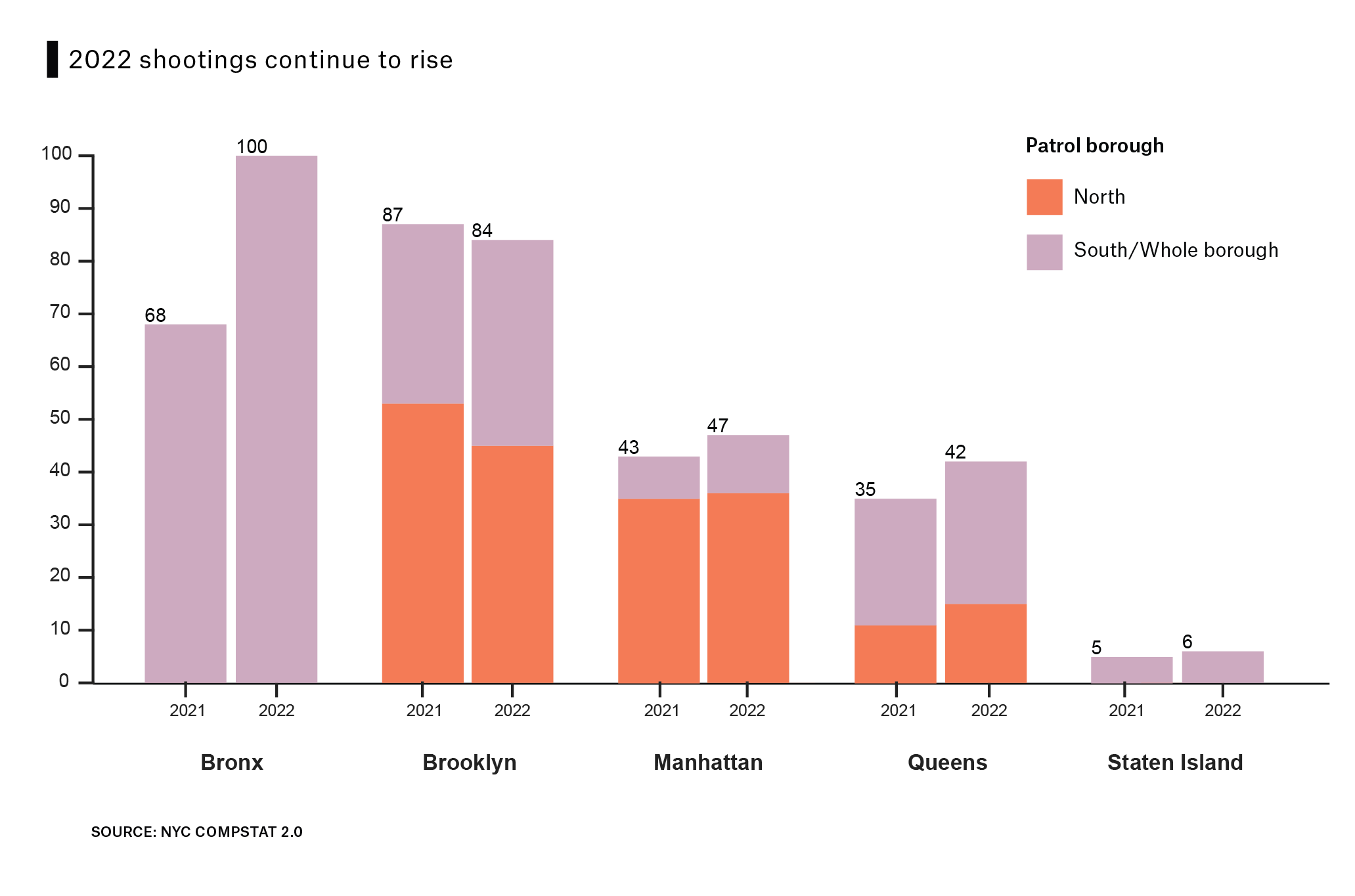

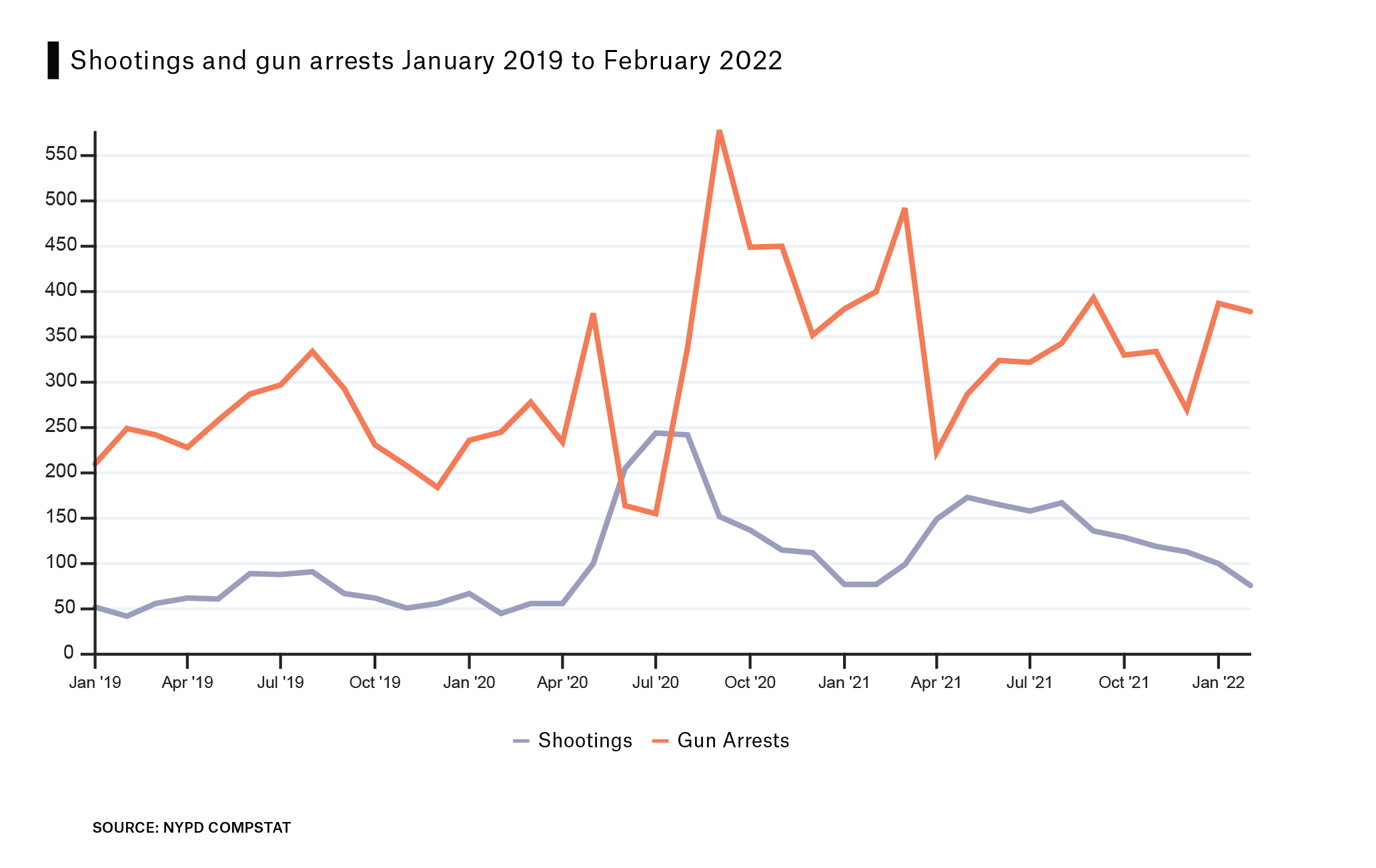

So, it wasn’t uncontroversial when Mayor Eric Adams followed through on a campaign promise and introduced new street units, re-christened Neighborhood Safety Teams. Adams says they reflect lessons learned: the police carefully chose officers for the new teams from a set of volunteers, provided them additional training, and will subject them to rigorous oversight. But that leaves unclear who (or what) the teams focus on, how they pursue their goals, and what measures they and the public should use to gauge their success, and Alcorn delves into all of this. Because the purpose of the street units is to reduce shootings — one of a “layered” approach the Mayor is advocating — we also provide some data, showing the concentration of shootings in a few neighborhoods and the trajectory of shootings since the beginning of 2020.

With shootings stubbornly elevated in the city’s poorest neighborhoods and even residents of its safest neighborhoods on edge, Mayor Eric Adams has reassigned hundreds of officers to “Neighborhood Safety Teams” that he says will go after guns and the people who use them. As he put it at a March 21 press conference: “We’re going to put violent people away. We’re going to remove the guns off our streets.”

Critics said the strategy was nothing but a revival of anti-crime units that NYPD disbanded in 2020, which had themselves absorbed a criticized Street Crime Unit in 2002. Adams insisted his teams would be different, donning uniforms instead of plainclothes, equipped with technologies that he said would allow them to more precisely identify people carrying guns, and trained in de-escalation, communication skills, and constitutional policing — principles so fundamental it would be concerning if officers haven’t already mastered them.

All the fanfare has left murky much about the new anti-gun teams’ eventual activities, the evidence guiding them, and the questions New York City’s journalists and lawmakers and voters should be asking in the months ahead to hold them accountable. Experts say the teams’ contribution to safety will be defined by who they are, where they go, what they do, and how their performance is measured and communicated to the public — and should be assessed against the safety that equivalent resources could buy in other ways.

What does an “anti-gun” team do?

Numerous police departments have stood up units overtly focused on gun violence — I interviewed dozens of them a few years ago for a study of proactive gun enforcement strategies — but their activities vary widely, making it hard to compare them. More important than what an anti-gun squad is called is what its members actually do.

Do they present in hot spots of frequent violence, whether to police minor quality-of-life crimes that contribute to perceptions of disorder, to conduct pedestrian or traffic stops, or to help residents solve problems and reduce opportunities for future crimes? Do they respond to shots fired and shootings in progress? Do they take a more investigative approach, drawing together evidence and intelligence from gun crimes across a precinct to identify and intervene with shooters and gun traffickers?

According to George Mason University professor David Weisburd, who edited a 2018 report on proactive policing published by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, “We know a lot about what will reduce crime, less about how to improve perceptions of the police, and very little about what will increase community well-being and solidarity.”

One of the teams is coming to northern Manhattan’s 32nd precinct, where anti-violence activist Iesha Sekou has long operated the organization Street Corner Resources. She recalled how the old anti-crime units would hunt guns by entering residences, throwing people against the wall, even handcuffing grandmothers to window-gates. But shootings in the precinct tripled from 2019 to 2021 and she sees addressing gun violence as imperative. “I’m not opposed to the teams,” she said. “I’m opposed to behavior that traumatizes and terrorizes our community.”

New York City’s leadership has offered shifting descriptions of the Neighborhood Safety Teams’ mandate. At the March 21 press conference, Commissioner Keechant Sewell said officers would use “laser-like precision” to go after “the relatively small number of criminals in our city who are responsible for the vast amount of violence,” a capacity seemingly attributable to facial recognition technologies and “new tools that can spot those carrying weapons.” (Technologies which should be fully disclosed to the public and subject to democratic legitimacy.)

But reporting by the New York Post indicated officers are hearing something different. “[Chief of Department Kenneth Corey] told us that he wants us to engage with quality-of-life infractions and criminals,” one unnamed supervisor in Brooklyn said approvingly. Cracking down on the low-level crimes of a large group of people is a world away from focusing on so-called trigger pullers. And the National Academies report concluded that this type of “broken windows” policing—addressing disorder to reduce serious crime—yields small to null impacts when it is spread diffusely across whole neighborhoods.

In theory, the Neighborhood Safety Teams could take a more investigative approach, like the Gun Team in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which Sgt. Joshua May conceived of and has led since June 2016. Its core mission is to proactively investigate gun crimes — following up on ballistics evidence, shots fired, recovered firearms — to crack down more consistently on shooters and traffickers. “I review EVERY gun arrest each day and track them from start to finish,” May emailed me recently.

Several years ago Tulsa, Oklahoma established a similar Crime Gun Unit and today it follows up on non-fatal shootings, which—aside from domestic violence—were not customarily investigated. According to Major Paul Fields, who oversees the unit (and was classmates with Commissioner Sewell at the FBI National Academy), its officers have been able to clear about a third of those cases. “When the [Crime Gun Unit] first started, it was kind of a hot spot unit, but we found that’s actually better left to patrol and street crime units,” he said. “We get more bang for our buck by looking at the data, finding out who are the most prolific shooters, and going after them.”

The experience of anti-gun units in other cities also demonstrates how missions can creep. In 2007, Baltimore, Maryland created two specialized units to focus on guns: a Violent Crime Impact Section deployed to shooting hotspots, and a now-disgraced Gun Trace Task Force that began by specializing in tracking crime guns back to their origins but ultimately degenerated into outright criminality, robbing and extorting the populace. It was ultimately disbanded and many of its members were convicted of federal crimes. The task force’s fall may be exceptional, but is an abject lesson about the damage a gun unit can do when there are temptations to cut corners and bend the rules.

Do the teams focus on places or people or guns?

New York City’s Neighborhood Safety Teams have been assigned to 30 precincts with among the highest rates of shootings, but that doesn’t clarify where within those neighborhoods they will spend the bulk of their time, nor what (or who) they will focus on.

The National Academies report found evidence that increasing police presence in hot spots generated short-term reductions in crime, as did problem-oriented policing—diagnosing and solving problems contributing to crime. But what police do in those locations matters, too. Pedestrian and traffic stops, even narrowly focused in crime hot spots, seem to undercut community trust. For years Durham, North Carolina operated a High Enforcement Abatement Team intended to “target problem areas, persons and crime trends” but it was dogged with allegations of racial bias in the stops it conducted and ultimately eliminated. NYPD’s own Operation Impact, which began in 2003 and ran for more than a decade, deploying additional officers to conduct stops in hot spots, reduced crime but only by ballooning the number of minor arrests. And in Baltimore, which prioritized stops and searches, there was insufficient oversight and training to prevent racial profiling, eliciting fear and distrust that were inconducive to public safety.

Johns Hopkins professor Daniel Webster, an expert in gun violence prevention who has studied policing in Baltimore, emailed: “it seems to me that the more place-focused you are (as opposed to person-focused), the more likely you will have unconstitutional stop and search practices affecting a lot of people. That doesn’t take place-oriented deployment off the board, it just means that you need additional measures to reign in problematic practices that will harm individuals and alienate communities.” Webster and his co-authors recommended the Baltimore police find empirical ways to estimate arrestees’ likelihood of violence involvement and ensure enforcement remains focused on people at highest risk.

How well do the teams play with others?

Although police often forget it, they don’t have a monopoly on creating public safety (research suggests they play a small if important role). Aaron Chalfin, an assistant professor of criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, said it would be important to know how the Neighborhood Safety Teams fit into the police department’s overall operations. “How do the units interface with or correspond with detectives and standard patrol officers? Is information exchanged?”

New York City also has a robust system of community-based violence interruption organizations that work in parallel but separate from the police, of which Sekou’s organization Street Corner Resources is a part. In the leadup to the launch of the anti-gun teams, she said she met twice with the local police commander but felt that the city’s outreach efforts were “kind of piecemeal.” That bothers her. “What does it say to police officers...when the community hasn’t been engaged enough in conversation?” Her staff regularly attend the precinct community council meetings and she hopes those will be a venue for detailed updates about the teams’ activities, the steps taken to limit collateral harms, and the impact on crime.

The teams’ relationships with the borough’s district attorneys could be equally important, as those bear crucially on how cases are resolved. In Chattanooga, Sgt. May said their gun team convenes with state and federal prosecutors each month to align on cases to prioritize. Webster noted that, particularly given New York City’s severe penalties for illegal firearm possession, it would also be important to track whether cases with lower-risk arrestees were getting downgraded or dismissed. “If the objective is to disarm and deter illegal gun carrying by the most dangerous people, is there some objective process to review the backgrounds of those arrested with guns?” he inquired.

Most essential, residents need to know what system of supervision and accountability exists to ensure that the Neighborhood Safety Teams are performing as advertised. The officers will be equipped with body cameras, but the city’s preceding anti-crime teams were involved in a disproportionate share of deaths including, most infamously, Eric Garner’s. “You can’t fix gun violence without help from residents,” said Barry Friedman, the director of NYU School of Law’s Policing Project, “and you can’t get it by going to war with the community.”

How is success measured, and against what alternatives?

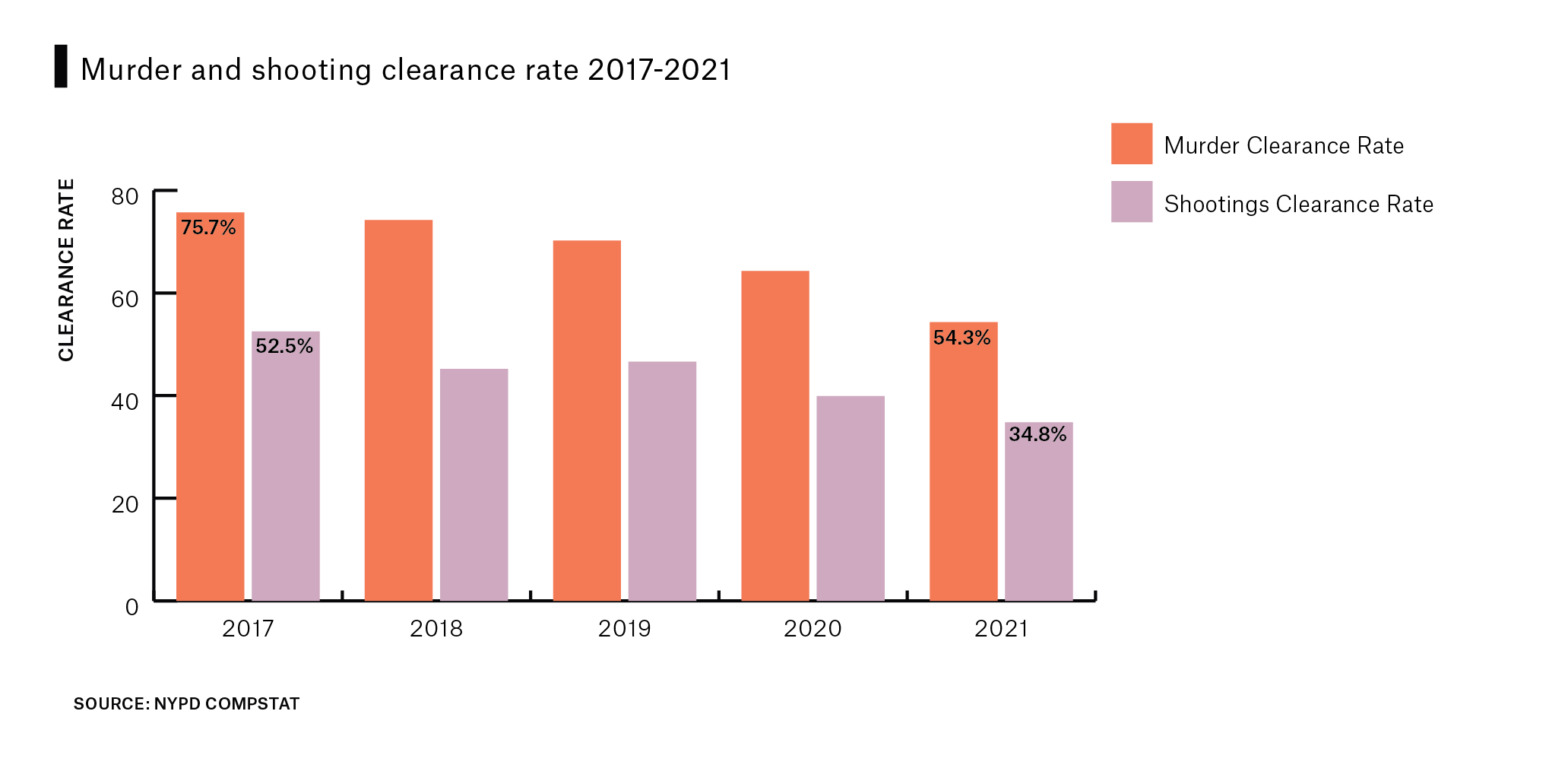

With the Neighborhood Safety Teams in operation just six days, Mayor Adams was already quantifying their success. “More than a gun a day was removed from our streets,” he boasted — although NYPD recovered more than 16 guns on an average day in 2021, according to the mayor’s own Blueprint to End Gun Violence. So, what are the most meaningful metrics for assessing the new teams?

Adams also touted 31 arrests made in the first program’s first week — but law enforcement and researchers say that this indicator isn’t meaningful on its own. In Baltimore, Webster and his colleagues found that arrests for gun possession weren’t associated with any local changes in the number of shootings. Chattanooga’s gun team prioritizes quality over quantity, said Sgt. May. “All gun arrests aren’t equal, so making sure we get the RIGHT people out of the way is key to our success.”

Perhaps most importantly, how are the teams performing compared to alternatives? Every dollar spent on policing is, de facto, a dollar for another public service forgone. Eric Cumberbatch, who founded and formerly ran the city’s Office to Prevent Gun Violence, told me it was vital to ascertain the cost of the new teams, and then to compare that to equivalent investments in social programs for the small group of people at elevated risk for perpetrating gun violence. Since the average take-home pay for a uniform officer in fiscal year 2020 was $99,000, just expected wages of the more than 400 cops ultimately assigned to the new units come to some $40 million a year. And after accounting for fringe benefits, which the NYC Independent Budget Office conservatively estimates as 50% of officers’ wages, their total cost will likely rival the $69-million network of non-police violence prevention initiatives that Cumberbatch oversaw.

Adams rightly pointed out that the Neighborhood Safety Teams are only “one layer” of the city’s response to gun violence. “People do not acknowledge the holistic approach that we are doing to stop crime.” He’s promised to expand summer employment opportunities to 100,000 youth and to extend violence intervention programs to 10 additional hospitals. There are other opportunities he could take fuller advantage of, too. The brief, school-based program Becoming A Man has been shown to significantly reduce arrests and increase graduation rates. Improved lighting in high-crime public housing developments causes dramatic, enduring reductions in crime. And the Department of Parks & Recreation has identified over 5,000 vacant and abandoned properties in the city’s most marginalized neighborhoods whose restoration would translate into improved perceptions of safety and reductions in actual crime.

Investments in alternatives to police are not insignificant, and have been growing. Cops tend to claim most of the credit when crime falls, and when it rises, to use that as justification for a budget increase. If New York City edges back from this current, precipitous rise in shootings, they’ll need to share the credit around.

Further reading

- Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities. (2018). Published by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.

- “Reducing Violence and Building Trust: Data to Guide Enforcement of Gun Laws in Baltimore.” (2020. By Daniel Webster, Cassandra Crifasi, Rebecca Wiliams, Marisa Doll Booty, and Shani Buggs.