What we can and can’t learn from Australia’s gun evolution

On a Saturday in late July, the main showroom of Cleaver Firearms was busy. Shoppers pored over custom-made armored glass cabinets or gazed up at walls bedecked with rifles and the taxidermied heads of a buffalo, dingo and banteng. The store’s scale is typical of a gun shop most anywhere in America — but here in northern Queensland, Australia, that makes it the largest gun retailer in the country.

Americans might be surprised to see so many firearms changing hands in Australia, said Jade Cleaver, whose dad founded the business nearly 50 years ago and is now at the shop running things most days. “The American perception,” he said, gesturing to the customers around him, “is this doesn’t exist.”

That’s because in U.S. debates about guns, Australia often gets pulled in to play the foil, the through-the-looking-glass, the what-if. For a time, the two countries followed similar trajectories: British Colonists spread across vast territories, violently displacing Indigenous inhabitants. Both countries developed cultural mythologies of life on the edge of settlement — the American “frontier” and the Australian “bush” — that prized toughness and self-reliance. And in each place, at the forefront of all of this were guns.

But after Australia experienced a terrible mass shooting in 1996, when a disturbed 29-year-old used two semiautomatic rifles to kill 35 people in the town of Port Arthur, the country did what some American gun violence advocates dream of: embarking on among the world’s largest mandatory gun buybacks and instituting a slate of new restrictions on the firearms that remained. Australian gun buyers must undergo a background check without exception, their purchases recorded in a state registry, with a 28-day waiting period before receiving the weapons in most cases.

After mass shootings in the U.S., Australian leaders have occasionally proffered their own course as an example to follow, and a string of Democratic Party standard-bearers have complimented Australia on its laws.

America’s gun death rate is 18 times higher than Australia’s, even though the supply of guns there is larger now than it was before the Port Arthur massacre.

But the reforms hardly put an end to Australian gun ownership. Indeed, the supply of guns is larger now than it was before the Port Arthur massacre, according to a recent analysis by the Australia Institute. There are over four million licensed firearms in the country, and the total has been steadily rising.

That trend, and pressure in some states to water down the existing laws, worries the rare local gun control advocate like Stephen Bendle, governor of the Australian Gun Safety Alliance. But Australia experiences just a fraction of the gun violence of the U.S.: 206 Australians died from firearm injuries in 2023, compared to over 46,728 Americans. Controlling for population, America’s gun death rate is 18 times higher.

Is there anything the U.S. can learn from Australia, a place where a significant gun supply coexists with far less lethal violence?

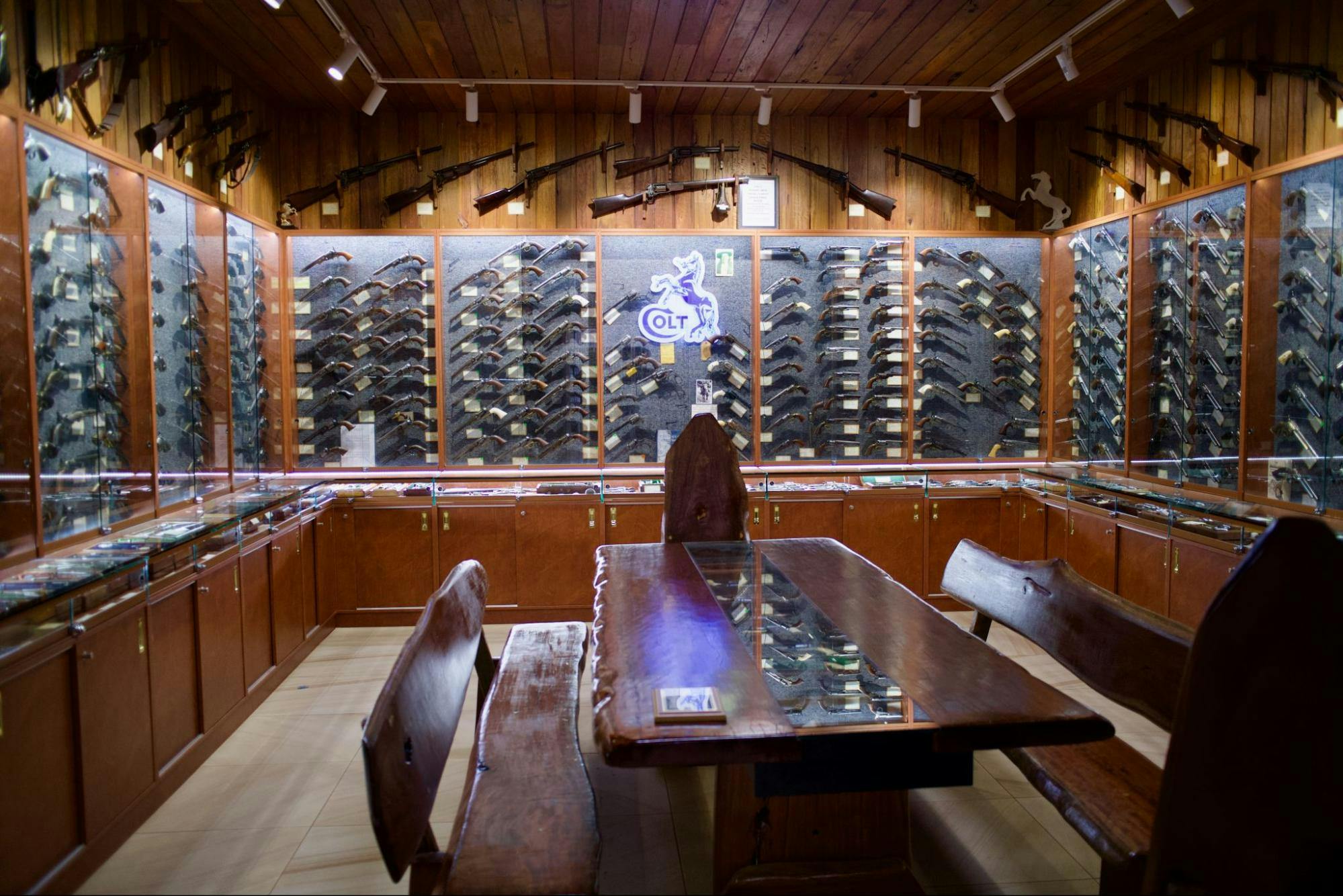

Few are more deeply versed in the country’s legacy of gun ownership or have a finger more tightly on its contemporary pulse than Cleaver. In one room of the store’s labyrinthine interior, he shows off his dad’s collection of 19th-century Colt handguns, many of them shipped to Australia in colonial times. There are sidearms used by the New South Wales Police, two original Walker pistols (of just a couple hundred in existence, according to Cleaver), three guns customized for Tiffany & Co. and an 1851 Navy revolver so early in its line of production that it bears a serial number of just a single digit. “This is Australian history,” Cleaver said.

He’s also brought the store into the modern era, building out a robust online business. Strolling with him through the store, we pass through a storage area where staff are preparing the hundreds of orders that ship out daily. Another room is lined with plastic bins containing purchase records. “There is 30 years of paperwork on that wall,” Cleaver says.

Gun ownership is less normative in Australia than in the U.S. — 1 in 30 adult Aussies have a license, whereas about 1 in 3 adult Americans are thought to possess a gun — and the reasons for ownership are different.

As part of the reforms instituted after the Port Arthur massacre, Australia requires would-be gun purchasers to articulate a “genuine reason” for buying a firearm and a “genuine need” for each gun. Under the law, “self-defense” is not an acceptable reason for firearm ownership. Most of Cleaver’s customers are recreational competition shooters or use guns for culling pests, he said. (Invasive species are a huge threat to the island country’s fragile ecology, from tubercular pigs to tick-carrying deer.)

Bendle, the gun control advocate, said this reflected a different vision of the meaning and utility of firearms. “We’ve never had the construct of, well, you know, ‘If we all have guns, we’ll be safer,’” he said.

Consistent with that, pistols are far less common in Australia than are rifles or shotguns: In New South Wales, the most populous state, they make up fewer than 5% of all registered firearms. Cleaver Firearms is an outlier in prominently displaying handguns; most gun stores in Australia keep them in a vault in the back or don’t offer them at all.

Australia requires would-be gun purchasers to articulate a ‘genuine reason’ for buying a firearm and a ‘genuine need’ for each gun — and ‘self-defense’ is not an acceptable reason.

That marks a stark contrast with the U.S., both in the threshold for buying a gun and the character of ownership that has thrived. In fact, over the last 25 years, the U.S. gun industry has pivoted away from hunters and recreational shooters to make handguns the primary product, overwhelmingly marketed to customers as a means of self-defense.

That, in turn, has been the handmaiden of policy change: The National Rifle Association and other organizations leveraged this shift to pass state laws allowing people to carry concealed, loaded guns outside the home, then won a crucial Supreme Court case that expanded the Second Amendment to permanently secure the right nationwide.

In Australia, even gun rights activists reject that vision. Graham Park, president of the country’s leading advocacy organization, Shooters Union, said purchasing guns for self-defense in the home should constitute a “genuine need,” since prohibiting that as an overt purpose leads to a great deal of legal fiction in which gun-buyers make up other qualifying reasons.

But he acknowledged there was little popular support in Australia for concealed weapon carrying outside the home. “I would hope that Australia doesn’t have enough violence that a lot of people feel the need to do that,” he said. “I’m not against it. I just think culturally, it’s not going to play here. And so why fantasize. If we’re not America, America is not us.”

Lawful gun owners bear too much stigma and too much regulation, Cleaver said, echoing familiar tropes from the U.S., albeit in an Australian vernacular. “Everybody is sick of the B.S. in this country of labeling the licensed shooter as the baddie who needs his guns taken off him,” he said. “They’re not the problem; the crims are the problem.”

But his attachment to his guns and opposition to gun laws didn’t seem as fierce or uncompromising as that of his American peers. He balked at calling all of this a gun culture — “It’s more of a hobby, a sport, a passionate pastime” — and even if he wouldn’t endorse some of Australia’s gun laws, he wasn’t dead set against them. Asked to gauge their acceptability on a scale from 1 to 10, he thought a moment before rating them a three.

“The regulations, if they’re applied correctly, then there is no issue,” said Cleaver. “The personal interpretation of a regulation is the issue.”

Park, similarly, disputed the impact of the Port Arthur reforms, pointing out that firearm deaths in Australia had been declining well before they were enacted. (The RAND Corporation, a nonprofit think tank, reviewed the evidence and, although it was difficult to tease out the laws’ effect from other factors, concluded that the strongest evidence was consistent with their “caus(ing) reductions in firearm suicides, mass shootings, and female homicide victimization.”)

Park nonetheless ticked off three categories of policy he said would lower misuse of firearms and associated injuries. “Background checks work,” he said. “Safe storage works.” And thirdly, “some type of safety training.” He just didn’t want to see the measures used “to punish or restrict gun ownership.”

A few weeks later, Americans woke up to a rare headline of firearm carnage in Australia, after a man in rural Victoria allegedly killed two police officers who were attempting to serve a warrant on him. The following day, attention shifted to a Catholic church in Minneapolis, where a 23-year-old opened fire on students and teachers during morning Mass, killing two children and injuring 18 other people. According to an analysis of data collected by the Gun Violence Archive, it was the United States’ 207th mass shooting of the year.

Sure enough, when Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz called for new gun regulations, he invoked Australia’s example. In the wake of Port Arthur, “They simply made changes,” he said. But in Minnesota’s divided legislature, it was not clear whether his package would have the necessary votes.