A review of recent political, judicial and intellectual debates related to gun violence.

The more we know about violence, the better we can address it—in theory.

But history shows that the public is easily spooked by the specter of crime, and debates over our response to it are largely influenced by the day's headlines and corresponding bursts of outrage and fear. Although evidence still plays a role, it can take on very different meanings depending on how it is framed.

Today—as U.S. cities weather a surge in shootings, as familiar adversaries contest reforms to the criminal justice system, and as new voices call for refashioning old debates about how to produce safety—there is great potential for change in how we address gun violence. But in what direction?

A few consequential conversations could decisively shape policy in the coming year.

As violence surges, criminal justice reform is a convenient scapegoat

Recent changes to New York state bail law shrank the number of people detained on Rikers Island, with further reductions still necessary if the facility is to be replaced with smaller borough-based jails. But hardly had the reforms gone into effect in January 2020, before they were subject to fierce criticism, and within months, the legislature had already rolled back some provisions.

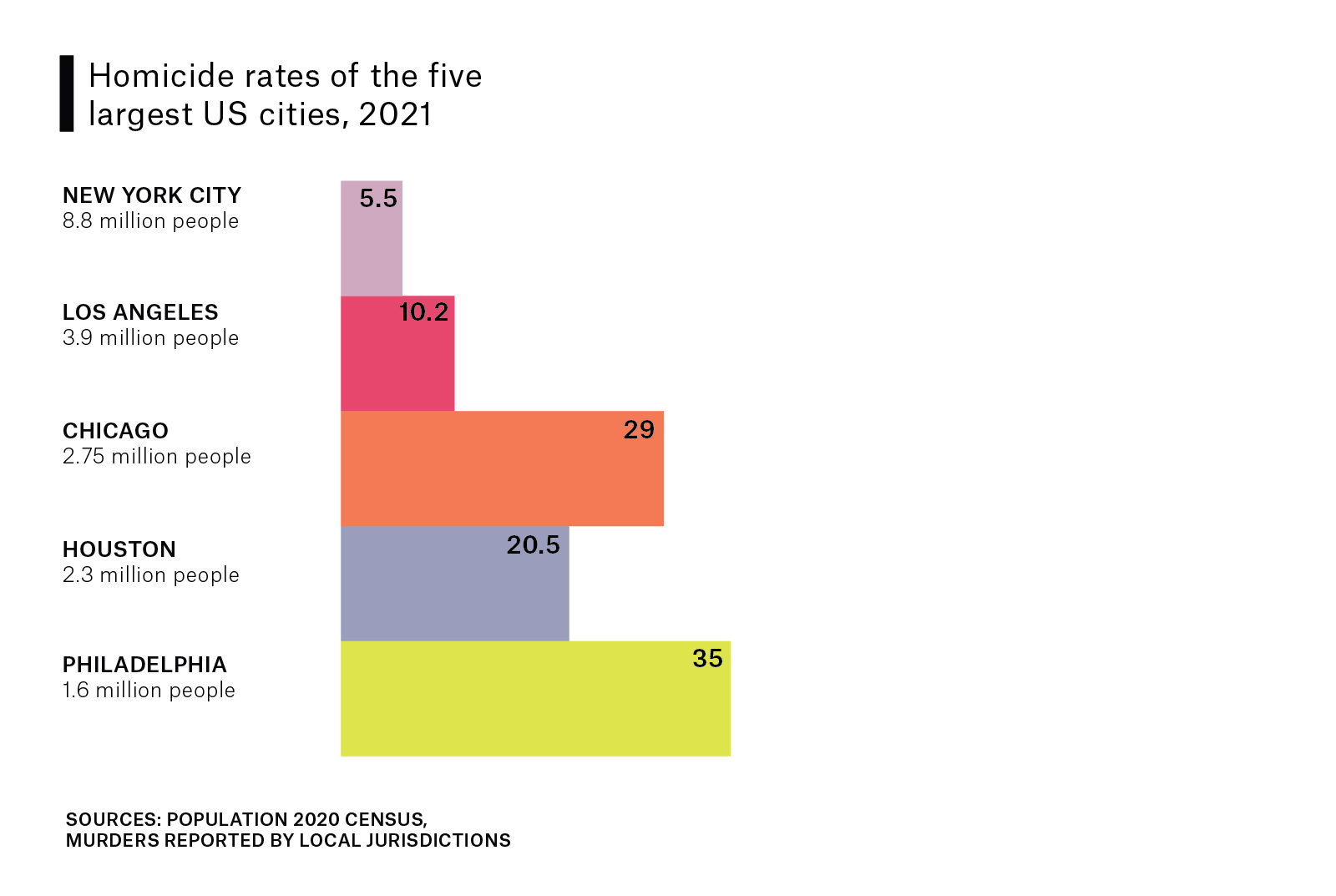

Then COVID-19 arrived, and with it, complex changes in crime across the country: many categories of crime fell sharply while shootings and murders rose. The regularity of these changes in nearly every U.S. city makes abundantly clear that factors beyond the control of any single jurisdiction played a major role. But some police and prosecutors in New York City seized on the local reforms as an explanation for the worrying uptick in violence.

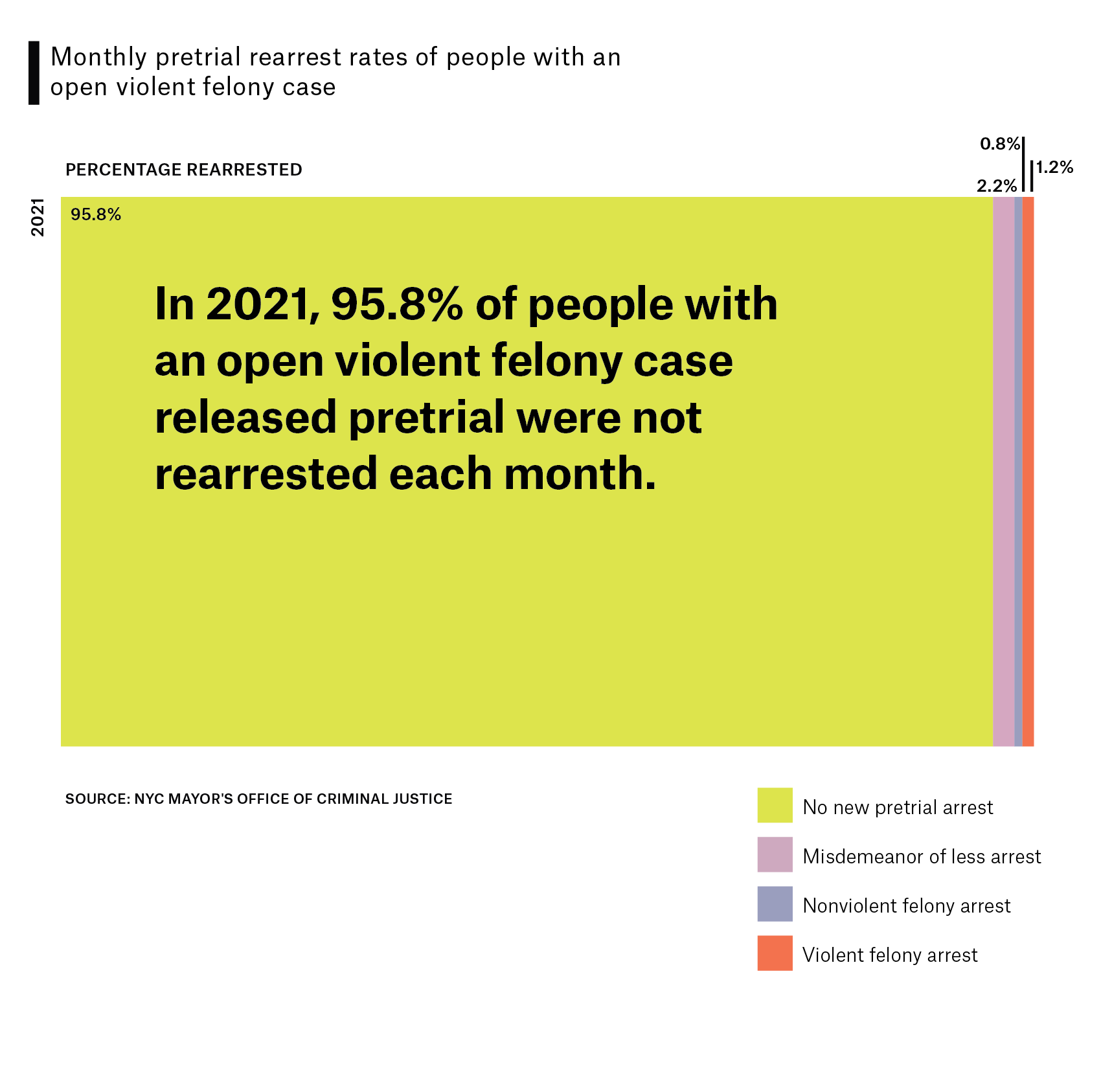

Reporting by the New York Post and data from the Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice show that only a tiny share of people on bail are re-arrested for violent crimes, so failure to incapacitate that group can't explain the vast majority of the increase in shootings. But that didn't stop top brass, current and former, from repeating the refrain. It remains an open question whether a pullback in policing and broader slowdown in court processes helped weaken communities' informal social controls that had kept violence at bay.

Dissecting the rise in violence and the consequences for the politics of criminal justice, Fordham professor John Pfaff suggests the pendulum of public opinion is swinging between progressive and punitive, but its ultimate direction is still unclear. Whether shootings remain stubbornly high or revert to pre-pandemic levels could be decisive in the narrative ahead.

Read more: The New Republic (Jun. 21, 2021) "Can Criminal Justice Reform Survive a Wave of Violent Crime?"

Is enthusiasm for community-based programs outpacing the evidence?

Having failed to secure a director for the country's top firearm regulatory agency, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and with little chance of passing new gun laws through a narrowly divided Congress, gun violence prevention advocates clung to a single tentative federal victory: inclusion of $5 billion for community-based anti-violence interventions in the House-passed Build Back Better bill, although its chances in the Senate have dimmed considerably. The eye-catching sum, though trivial compared to some $120 billion state and local governments spend on policing each year, would be a huge increase in non-law enforcement approaches.

So, does the science support this investment? When writer German Lopez looked at research on one focal element, the training and deployment of violence interrupters, social scientists told him the evidence was "mixed" or "weak." John Jay College research professor Jeffrey Butts, among the leading evaluators of the approach, worries that community-based programs have "become a movement as opposed to a strategy or an intervention plan." We needn't invest more in law enforcement, he added, and a raft of non-police approaches show promise (as documented in a 2020 report he co-authored). But he'd like to see social scientists "nailing down exactly how to make these programs effective."

Policymakers don't seem to share his caution. Eager to harness federal largesse, cities and states have announced major investments in public health approaches to violence—$15 million in Indianapolis, $30 million in Michigan, $45 million in Wisconsin, $50 million in Baltimore—though often without specifying exactly how it will be spent. What operations get stood up and whether they will be carefully evaluated remains to be seen.

New York City's new mayor, Eric Adams, has promised to fully fund the city's Crisis Management System, a $42 million network of community-based anti-violence organizations, and increase funding for the City's Office to Prevent Gun Violence. No matter the level of investment, violence interruption is only likely to be a partial answer to the question of how to prevent violence while also reducing dependence on police.

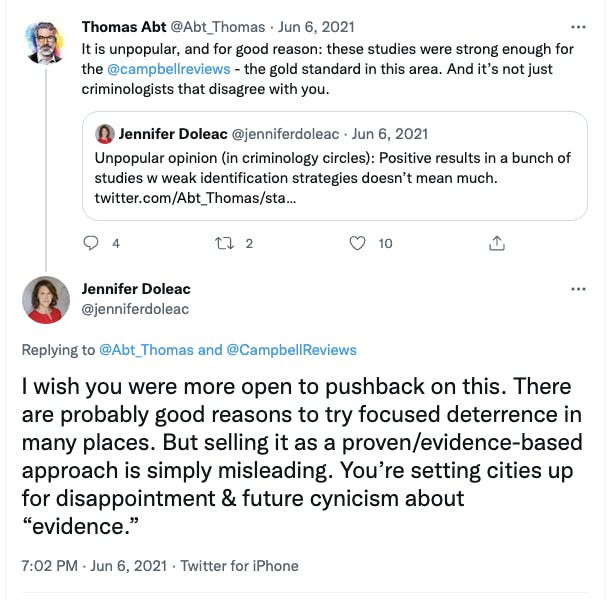

Debating the efficacy of vying approaches is perennial and not confined to violence interruption. Economist Jennifer Doleac and self-described "crime nerd" Thomas Abt tussled over the acceptable standards of evidence for evaluating focused deterrence, despite a recent review suggesting consistent, significant effects.

Read more: Vox (Sep. 3, 2021) "The evidence for violence interrupters doesn't support the hype"

Fissures in the credibility of police and policing

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, which the Minneapolis Police Department originally mischaracterized as a "medical incident," journalists nationwide contemplated whether they should rethink how to use information provided by police.

In New York City, public defenders and advocates have increasingly condemned the New York Times' coverage of crime and public safety for what they say is pro-police bias in selection of sources and framing of stories. They've been particularly vociferous when stories overstate recent increases in crime or imply that the only solution is more police. In contrast, conservative political commentator Heather Mac Donald has groused that when the paper covers public upset following police shootings, it downplays violence perpetrated by protesters and upbraids police for racism.

The impact this clamor has on newsrooms themselves is unclear, although media outlets are reassessing their crime coverage more generally. For example, as of June 2021, the Associated Press will no longer name suspects charged with minor crimes. They have also sought to purge the vague term "officer-involved" from coverage of shootings by police, though newsrooms haven't done so.

Law enforcement certainly aren't ingratiating themselves with their critics when they use crime data strategically, and sometimes duplicitously, to shape the public narrative. Former Police Commissioner Dermot Shea repeatedly cited New York City Police Department (NYPD) data to attack the state's recent bail reforms, only backtracking once contradictory data were publicly available.

Underlying all this is a push and pull about the fundamental purpose and legitimacy of police themselves. Brooklyn College sociologist Alex Vitale, who advocates for police abolition, titled his book The End of Policing—whereas blogger Matt Yglesias, a critic of Vitale's writings, has not been shy in arguing that the United States should invest more in policing rather than less.

Abolition might be better viewed as a compass than as a map: there's broad support for reducing the touch of the criminal justice system, but we do not know the precise path to get there. The tea leaves of an off-year election are few and ambiguous, but Minneapolis' notable rejection of a Nov. 2021 ballot measure to eliminate its police department is a reminder that those who would abolish penal institutions face a steep uphill climb.

Read more: The Appeal (Jun. 22, 2020) "The bumpy road to police abolition"

Unlikely alliances seek to loosen gun laws

In recent arguments before the Supreme Court that could presage massive changes in whether communities can restrict the public carry of hidden, loaded firearms, gun rights advocates got an assist from an unusual quarter: Black attorneys of New York City's public defender organizations.

For more than a generation, gun rights advocates have strategically promoted gun carrying nearly everywhere by nearly everyone, whether through communications campaigns or by lobbying state and federal lawmakers or by supporting litigation. This fall, a lawsuit brought by the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association reached the highest court of the land, and the court's newly conservative makeup seems ready to brush away remaining restrictions.

Yet one of the most discussed amicus briefs in the case was submitted by the public defenders, who highlighted not the benefits of gun carrying but the harms of its criminalization. The attorneys contended that their clients have legitimate desires to carry guns in the city yet are subject to arrest and incarceration.

Some saw the brief as a misguided alliance, one that accepts at face value dubious arguments that public carrying of firearms increases individual and community safety.

But with gun ownership rising among minorities both before and during the pandemic, progressive Black and Brown advocates could increasingly make common cause with gun rights activists. The diversity of callers to Brian Lehrer's radio show about the case hinted that there could be more New Yorkers interested in carrying than one might expect. And the argument is echoing elsewhere: Detroit's Neighborhood Defender Service subsequently released its own data showing growing racial disparities in arrests for carrying a concealed weapon.

If the court scuttles New York state's restrictive public carry laws, as expected, and that precipitates a significant uptick in public gun carrying, it could have implications for violence and also for NYPD's gun-centric anti-violence strategies.

Read more: The Nation (Jul. 26, 2021) "Why are public defenders backing a major assault on gun control?"

The city's newest progressive prosecutor thinks twice about guns

When, in his first week as Manhattan district attorney, Alvin Bragg issued a memo to his staff outlining changes in how the office would treat people arrested with guns, he may have believed it would be accepted without comment. After all, he'd campaigned on the promise of making pretrial detention and post-conviction incarceration the exception, including for people arrested with guns so long as they were not clearly "drivers of gun violence."

But in January 2022, on the cusp of becoming a reality, that commitment sounded differently, particularly with Manhattan shootings reaching levels not seen in over a decade. "Happy 2022, Criminals!" the New York Post announced; police union heads objected, and by week's end, the city's new police commissioner Keechant Sewell was pushing back hard. It only added fuel to the flame later in the month when two police officers were gunned down in Harlem. By February, Bragg had reversed himself, designating felony prosecution as the default for gun cases, and announced the appointment of veteran attorney Peter Pope to oversee the office's work on gun crime.

Even this backpedaling wasn't enough for some. Charles Fain Lehman, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, wrote that decarcerating "necessarily means releasing violent or serial offenders back onto the streets," continuing, "While Bragg has taken a step in the right direction, he has miles still to go."

Bragg's original intentions seemed clear. The risk posed by someone in illegal possession of a gun is self-evident, and research shows that illegal gun-carrying is associated with much higher risks of perpetrating violence and being victimized by it. But as noted legal commentator Emily Bazelon put it, "not everyone who carries a gun is a shooter," and directing all such arrestees into long prison sentences can fully derail the lives of people who might have changed their behavior in response to less punishing and less costly programs.

The question of how to assess young men arrested with guns, to offer effective alternatives to incarceration to some of them, and to sell the public on this new arrangement has bedeviled progressive prosecutors across the country. Bragg is hardly isolated in his ambitions: Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez has operated small but successful diversion programs for first-time gun offenders, and last fall, the University of Chicago catalogued similar prosecutor-led diversion programs in eight cities.

But Bragg's experience suggests that those promoting greater nuance and leniency may find themselves in retreat. ◘