America’s obsession with guns isn’t organic. It was manufactured.

At the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition on July 12, 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented a lecture to the American Historical Association titled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” It hardly mattered that the West was at that point barely “history” — the U.S. census had only declared the frontier “closed” three years prior. A unified American identity was a post-Civil War necessity, and Turner thought he had captured it. The taming of the West was the crucible that yielded a sturdy, self-reliant American character.

For the less high-minded, one could witness the birth of that character in another form at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, just outside the World’s Fair grounds. Dubbed “purely and distinctly American” by Mark Twain, the spectacle, scripted for the viewing pleasure of thousands of onlookers, was meant to dramatize the intersection of savagery and civilization. There were Lakota warriors in feathered regalia, settlers staving them off, cavalry charges and a sharpshooting act featuring Annie Oakley. Winchester rifles cracked, Colt revolvers spun, and the West was won, over and over again, thanks to rugged Americans armed with guns.

Both Turner’s simplistic expository and Bill Cody’s embellished exposition were deeply influential in shaping the larger tale America tells about itself. But neither went so far as to claim that guns had won the West. That task would be left to admen at the leading gunmaker Winchester, who marketed the company’s flagship lever-action rifle as “The Gun That Won the West” to a postfrontier audience eager to be a part of an emerging American identity. These marketers didn’t seek to intellectualize history, nor to dramatize it. They aimed to brand it.

And did they ever succeed. So much of what we think of today as an absolute truth — that guns are integral and essential to the nation we know — was forged by gunmakers and marketers that, time and again, were eager to create demand by shaping the United States’ very sense of itself. Those of us grappling with the consequences need to understand what made those early gun marketers geniuses of an emergent field, and we need to appreciate how their successors have only gotten more savvy and cynical in the modern era, suffusing a political debate with a mythology of their own making.

***

Around the time of the “Gun That Won the West” campaign, manufacturers like Colt and Winchester had a challenge: how to pivot from military production to peacetime consumerism. The answer, they determined, was to build an emotional economy, associations with guns that included nostalgia, masculinity and patriotism. It is what historian Pamela Haag calls the “industrialization of myth,” and it would place firearms at the center of the American story for a century.

These early admen were canny in understanding that they needed to tell a story. So they gave their products not just model numbers, but names. When you bought a “Peacemaker,” Colt’s iconic revolver, you got a newly manufactured gun with a built-in history. In ads, manufacturers touted American battlefield pedigree — Union soldiers frequently carried Remington and Colt revolvers, while Winchester’s lever-action rifles had supplied scouts and militias in the West. Each peacetime invitation for sale was a portrait of rugged individualism in a violent past, sometimes literally: Winchester calendars featured lush paintings by Frederic Remington depicting cowboys and Native American warriors locked in dramatic battles, while Smith & Wesson lithographs portrayed settlers heroically defending their homesteads. These weren’t just ads for guns, they were opportunities to purchase an heirloom of manifest destiny.

The persistent idea that firearms are central to our character is, in the end, a marketing lie agreed upon.

Along the way, gun industry marketers took advantage of the burgeoning pulp folklore of the West, leaning heavily on real-life figures like Buffalo Bill, Bat Masterson and Wild Bill Hickok — and their tales of gunplay. These men, heroes and performers alike, were the influencers of their day and lent credibility to reliable firearms as part of the myth. Their endorsements, both tacit and explicit, turned firearms into aspirational commodities, a way of buying frontier courage and a piece of Americana.

Haag characterizes this time for the gunmakers as “a transition of imagining a customer who needed guns but didn’t especially want them to a customer who wanted guns, but didn’t especially need them.” The emergent industrial gun sector was melding myth and customers in the same crucible. No wonder, then, that at the 1893 World’s Fair — dubbed by many as “the fair that changed America” — Smith & Wesson was sure to have hundreds of its guns on display and ready for sale.

***

Americans’ relationship with this dangerous product was set in motion with the culture taking shape alongside it. But the partnership wasn’t entirely self-sustaining. In each generation, marketers had to find ways to rekindle the romance. And they did.

During World War II, the war effort and nationwide rationing required gun manufacturers to mostly set aside the civilian market. But that didn’t stop the industry from running ads to past and future customers. The makers of military guns knew that on the other side of lucrative government contracts, they would need a civilian market, so they ramped up ads tying their brands to American valor in the European and Pacific theaters, associating hunting and sport shooting with war readiness and capturing a wistful longing for an American pastoral interrupted by global conflict.

Winchester, for example, featured paratroopers in battle with M1 carbines, under the headline, “Relying upon Winchester is an Old American Custom.” The ad reminded readers that Winchester had been “On Guard for America Since 1866” and used this legacy to assure future consumers that Winchester would still be there after the war — for sport, for family, for freedom. While other kinds of products also leaned into wartime imagery and patriotism for solidarity and sales, ads for Coca-Cola couldn’t lay claim to being “battle-proven” at Iwo Jima, as the Winchester M1 marketing did. For its part, Remington ran an ad featuring a tired, homesick soldier longing to go hunting again. It promised its customers on the homefront that, after the war was won, it would again be serving sportsmen with shotguns, rifles and ammo.

In the postwar years, with a flood of returning GIs, military-surplus rifles and excess manufacturing capacity, the industry found a ripe opportunity to sell nostalgia. The M1 Garand and other service-style rifles were repackaged as heirloom-grade sporting rifles. Ads encouraged veterans to bring their wartime marksmanship into the American wilderness — or to pass that skill on to their sons as both a pastime and a future preparation.

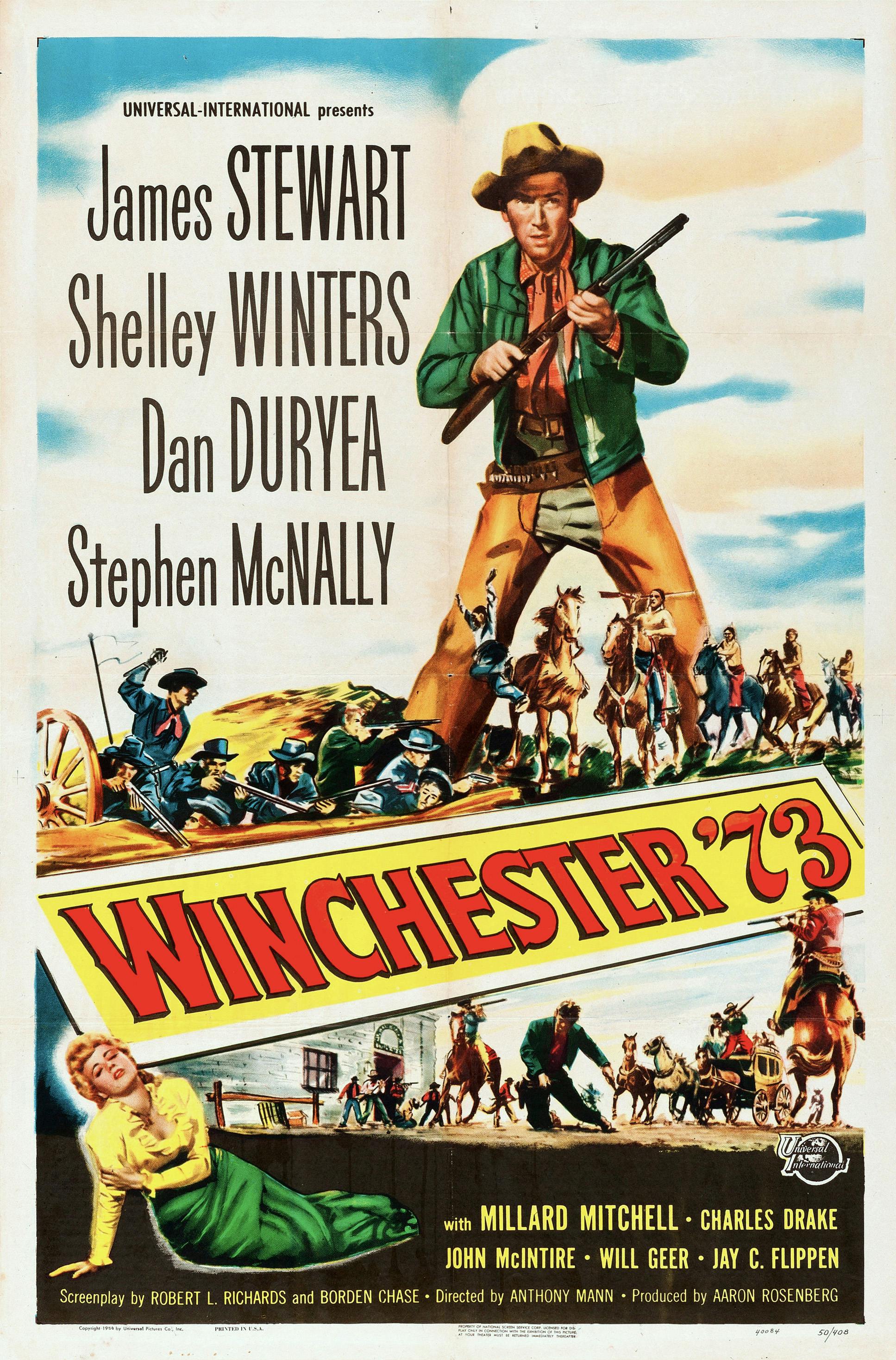

Meanwhile, with a double dose of Westerns and WWII epics, Hollywood did its part to canonize American valor and the weapons used to obtain it. There are simply too many examples to list here, but if you know that the Winchester Model 1873 was “The Gun That Won the West,” that might have something to do with Jimmy Stewart cradling one in “Winchester ’73,” the 1950 film that made the rifle talismanic. The film personifies the object worship that characterizes much of the gun industry’s marketing strategy, a story of a gun coveted both on-screen and in the audience. Winchester supported the movie and leaned into the synergy: It created marketing schemes to leverage the film while its catalogs reproduced stills, using the gun’s cinematic legacy to solidify its real-world brand as an American icon. Winchester would later capitalize on silver-screen exposure in “To Hell and Back” (1955), which stars real-life war hero Audie Murphy as himself, dramatizing his extraordinary battlefield exploits — most often with an M1 carbine — including the time he took on an advancing German unit on his own. The film, which was Universal’s most lucrative until “Jaws” two decades later, was a silver screen update to Remington’s painted platonic ideals: A plucky American and his rifle can single-handedly defend freedom from the advancing hordes. The man and the gun meld; maybe you, too, can get Murphy-level grit when you buy his gun.

By the early 2000s, guns were firmly ensconced in the stories America told itself. Still, the gun industry nevertheless faced shrinking interest in firearms. For one, an increasingly urban America was losing interest in hunting, impacting sales of rifles and shotguns. The industry’s pivot to pushing handguns misfired, sparking backlash and lawsuits stemming from the widespread gun violence of the ’90s. Overall, households with guns dropped from around 50% in the late ’70s to less than one-third at the turn of the century. Americans, it seemed, did not need, nor particularly want firearms.

Then came the horror of 9/11, delivering a new crucible for American identity, along with two prolonged conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The gun industry, seizing an opportunity, once again pivoted — this time not to meet military needs, but to profit on wars being fought by a volunteer army and televised to the unenlisted.

The national moment coincided with the expiration of the federal assault weapons ban, presenting gun manufacturers with a massive opportunity. For the first time in a decade, they could freely market civilian versions of the latest military-style rifles. And they did so aggressively. Goodbye Winchester and the gun your grandpa’s grandpa used to win the West; hello AR-15, a semiautomatic twin of the military M4, just like the ones used by modern warriors to conquer terrorism in the Middle East. The “AR” stands for Armalite — the original manufacturer — but the gun industry saw a time-tested opportunity to co-opt patriotism and rebranded it “America’s Rifle.”

For the next 20 years, gun manufacturers would continue to tap into this emergent special ops, “tacti-cool” aesthetic and were happy to offer middle-management types elite association through sophisticated weaponry. No mere hat tip to distant conquest, now valor was for sale with ads promising that customers could “Use What They Use” or own “a piece of the new U.S. warfighting next-gen kit.” Another marketed “the world’s most battle-proven rifles.”

Gun marketers have only gotten more savvy and cynical in the modern era, suffusing a political debate with a mythology of their own making.

Manhood was another critical American attribute that apparently needed to be reclaimed in the modern era, as ads said that you could have your “man card reissued” by buying an AR-15. You could become an “Alpha” and “never (be) a victim, always a victor.” If early gun ads were selling an instant fix of nostalgia for a violent, bygone frontier, the new era of marketing puts you in the battle and sets up a dangerous innuendo: Use the guns that are fighting the “savages” abroad to resist the “savages” at home. The ads conveniently let you decide who is the “savage” in the crosshairs. “Not Today Antifa” barks one ad from Spike Tactical. “Forces of opposition, bow down,” declared another one from Bushmaster, a brash subsidiary of Remington.

Just as in the past, the companies needed validation from real characters to sell the fiction. While dramatized ads overlay battle rifles, flags and freedom, plainspoken and practical returning soldiers now vouch for the weapons and their efficacy on social media — with demonstrations garnering hundreds of millions of views that make Buffalo Bill’s act look like a sideshow. YouTube personas Garand Thumb and IraqVeteran8888 display for their young male audiences battlefield proficiency while reviewing the latest firearms from Sig Sauer and Springfield Armory. It hardly matters that some of the content is gun industry-sponsored and some is purely organic: The authenticity is ever present. And the testimonials echo the bona fides of the past. Wild Bill Hickock preferred to carry a pair of .36‑caliber Colt Navy revolvers; YouTube’s hickok45, with his 8 million subscribers, prefers a .40-caliber Glock 23.

As online personalities akin to those who help market beauty products or tech gadgets demonstrate the lethal functionality of a new generation of firearms to a new generation of buyers, the modern industry capitalizes on a quintessentially American attribute: individuality. There are endless configurations of parts and accessories to make the firearm you purchased distinctly yours. Gunmakers are happy to sell you rail systems, sights, scopes, grips and camouflage finishes for the stateside tactical warrior who didn’t so much need a gun but wanted one so he could be part of something bigger. And the more individualized the gun, the less it is a tool and the more it is a part of you. Try taking that away.

The new era of marketing sets up a dangerous innuendo: “Use the guns that are fighting the ‘savages’ abroad to resist the ‘savages’ at home.”

The gun industry’s multigenerational marketing campaign has always been about selling weapons, but its true triumph lies in how it has shaped the political and public safety debate. “Both sides” now seem to accept — if sometimes grudgingly — that guns are intrinsic and immutably American, essential to our history and endemic to our body politic.

But are they? We might do well to admit that, as a country that nearly destroyed itself a century after its founding, we forged a national identity around resiliency, endlessly recommitting ourselves to the ideals of freedom and individuality. Yet each time America sought to define or redefine itself, there was the gun industry drafting off our collective story, standing next to heroes real and fictional, edging ever further into the frame.

The persistent idea that firearms are central to our character is, in the end, a marketing lie agreed upon: American fortitude and love of liberty spring not from our fundamental character, but from an inanimate object that periodically goes on sale. The truth is that we might actually be a country that sometimes needs guns, but that needn’t especially want them. We’d do well to not mistake the folklore of the firearm for our true grit.